Forged in Steel: The Evolution of Medieval English Armour

England, a land whose rich history is woven from countless threads of human endeavor, conflict, and innovation. The medieval period, spanning roughly from the 5th to the late 15th century, was a defining era in English history. It was a time marked by significant social, political, and technological transformations.

One of the most iconic figures to emerge from this period was the knight. The knight was not merely a warrior but a social class, a symbol of feudal duty, and an embodiment of the chivalric ideals that shaped medieval society. Central to the knight's role and identity was his armour. Armour was more than protection in battle; it was a statement of status, craftsmanship, and the technological prowess of the age.

In this article, we will look into the evolution of medieval armour in England. We will explore its origins, trace its development over the centuries, and examine the intricate craftsmanship that made it both a practical defense mechanism and a work of art. Our journey will shed light on how armour impacted the changing needs of warfare, the advancements in metallurgy, and the social hierarchies of medieval England."

Origins of Medieval Armour

To understand the evolution of medieval armour in England, we begin with the early 11th century, during the late Anglo-Saxon period. At this time, England was a mosaic of kingdoms, each with its own customs and military practices. The typical Anglo-Saxon warrior relied on relatively simple protective equipment compared to later standards.

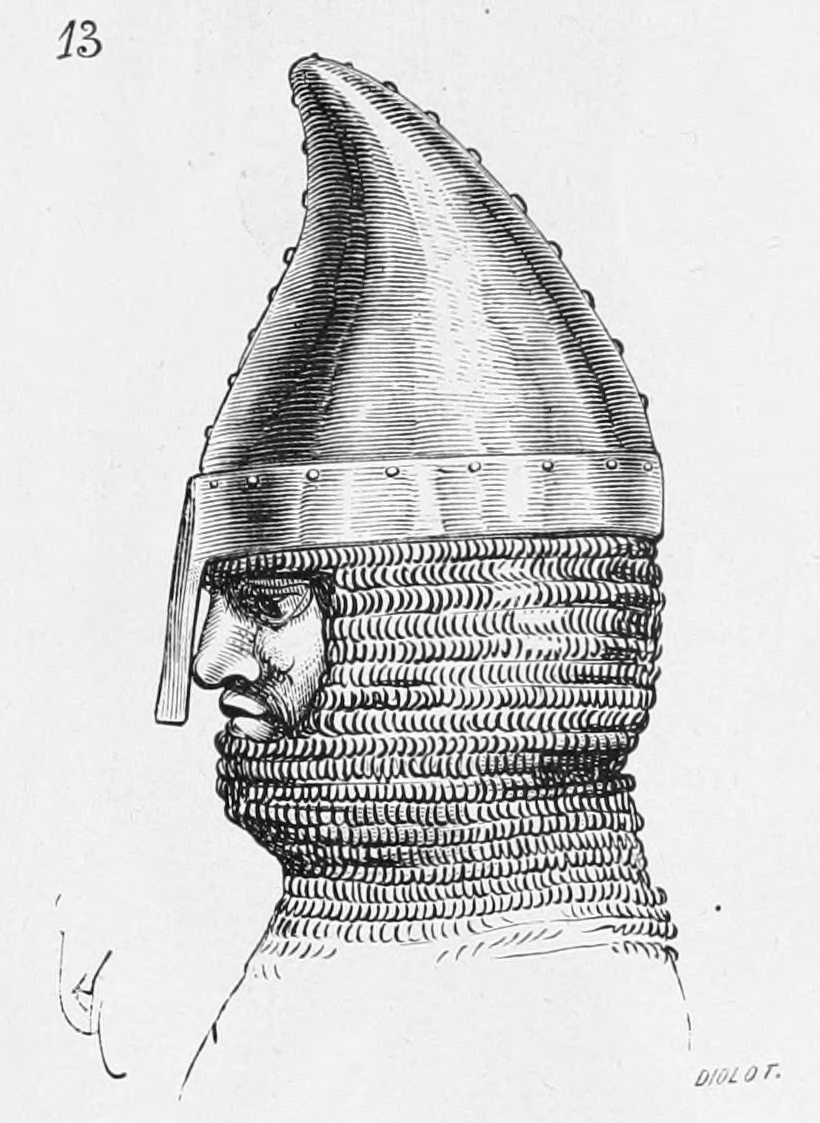

Helmets were fashioned from iron or hardened leather. The most common type was the conical helmet with a nasal guard, offering basic protection but leaving the cheeks and neck exposed. The primary body protection was the gambeson, a padded defensive jacket made from layers of linen or wool. The gambeson provided cushioning against blows and was worn under mail or plate armour in later periods to prevent chafing.

Shields were crucial defensive tools. The Anglo-Saxon shield was typically round, made from wooden planks glued together and covered with leather or rawhide. A central metal boss protected the hand grip. Shields were not only functional but also displayed personal or group identity through painted designs.

Weapons of the time included spears, axes, and swords. The limitations of their armour meant that Anglo-Saxon warriors relied heavily on shield walls—tight formations where shields overlapped to create a defensive barrier.

In 1066, the Battle of Hastings dramatically altered the course of English history. The Norman invasion, led by William the Conqueror, introduced new military tactics and technologies. The Normans brought with them more advanced forms of armour, most notably chainmail.

Chainmail, or 'maille,' was a significant technological advancement. Constructed from interlocking iron rings, each riveted or welded shut, chainmail provided superior flexibility and coverage compared to the rigid leather or padded armours. A chainmail hauberk—a long shirt of mail—often extended to mid-thigh or knees and included sleeves. Some hauberks featured an integral coif to protect the head and neck.

The production of chainmail was a labor-intensive process. A mailleur (chainmail maker) would create wire by drawing iron through progressively smaller holes in a drawplate. The wire was then coiled around a mandrel to form a spiral, which was cut to produce individual rings. Each ring was linked with others and then riveted shut. A typical hauberk contained approximately 20,000 to 30,000 rings.

Chainmail offered significant advantages. Its flexibility allowed for greater freedom of movement, essential for knights who fought both on horseback and on foot. The interlocking rings distributed the force of slashing blows over a wider area, reducing the risk of injury. However, chainmail was less effective against piercing weapons like arrows or thrusting spears, which could force the rings apart.

The introduction of chainmail also had social implications. The cost of materials and the time required to produce chainmail made it expensive. As a result, it became a symbol of wealth and status. Only nobles, knights, and wealthy individuals could afford such armour, reinforcing the class distinctions of the feudal system.

Norman influence extended beyond the battlefield. They established new social structures, including the feudal system, which formalized the roles of lords and vassals. Knights were granted land in exchange for military service, and their armour became a visible sign of their obligations and privileges.

The period following the Norman Conquest saw English armourers beginning to adopt and adapt chainmail production techniques. Over time, chainmail became more widespread, though it remained expensive. Armourers experimented with different ring sizes and patterns, seeking to balance protection, flexibility, and weight.

Despite its advantages, chainmail had limitations. It provided little protection against blunt force trauma. A heavy blow from a mace or war hammer could cause serious injury despite the mail. Additionally, chainmail offered limited defense against the increasing power and prevalence of ranged weapons.

These challenges set the stage for further innovations in armour design, leading to the gradual incorporation of plate elements. The evolution of armour was a continual process of adaptation to new threats and technologies, reflecting the dynamic nature of medieval warfare.

The Transition to Plate Armour

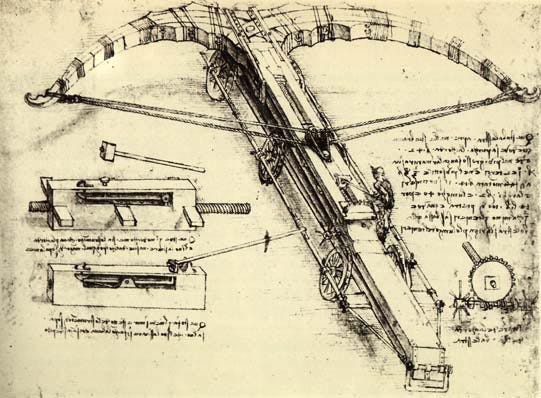

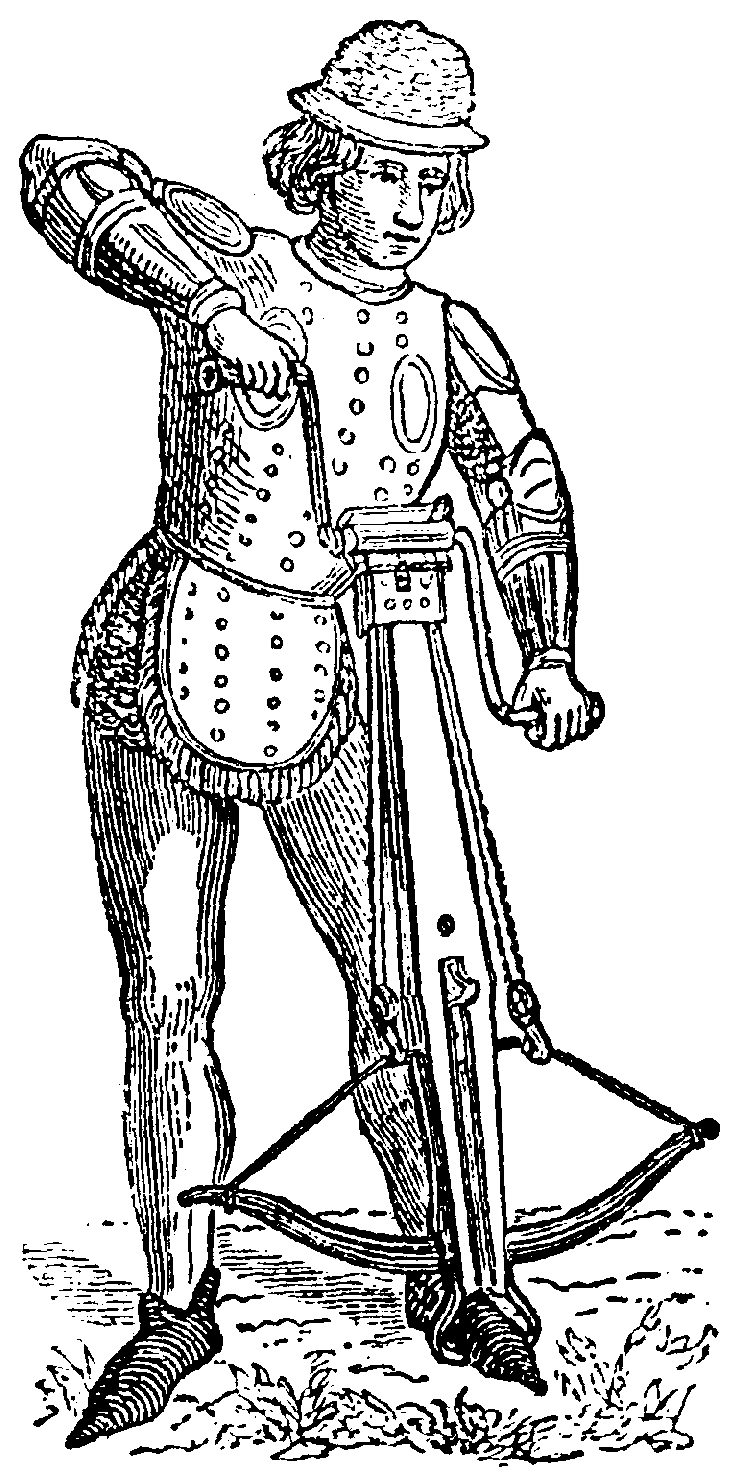

The 13th century marked a pivotal era in the evolution of armour. Advances in offensive weaponry, particularly the widespread use of the crossbow and the advent of the English longbow, introduced new challenges. These weapons could deliver bolts and arrows with sufficient force to penetrate chainmail, especially at close range or with specialized arrowheads like the bodkin point.

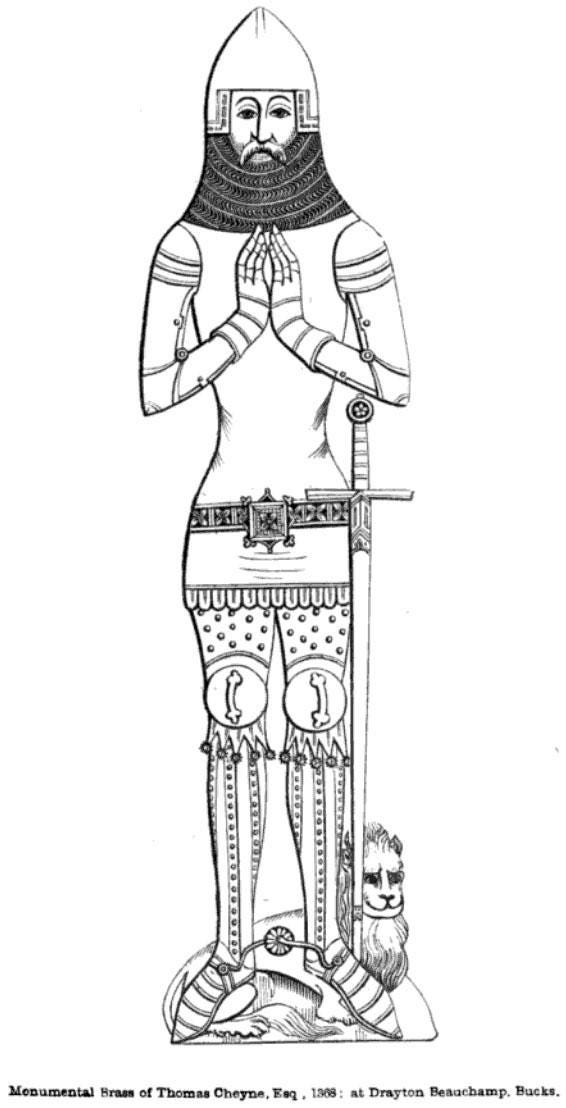

In response, armourers began to reinforce chainmail with rigid steel plates over vulnerable areas. This transitional armour, often referred to as 'transitional harness,' included key developments such as poleyns, which protected the knees, and coudes, guarding the elbows. Greaves were added to shield the shins and calves, while gauntlets safeguarded the hands without sacrificing dexterity. These plate additions were typically worn over chainmail and attached with leather straps or integrated into the mail itself. They were anatomically shaped to conform to the body's contours, enhancing both protection and mobility.

Another significant innovation was the development of the coat of plates. This garment consisted of multiple small steel plates riveted inside a fabric or leather covering, providing substantial protection to the torso. It was a precursor to the solid breastplate and represented a major step toward full plate armour.

Advancements in metallurgy were crucial during this period. Armourers benefited from improved methods of iron production, such as the use of water-powered hammers and blast furnaces. These technologies allowed for the production of larger, high-quality steel plates. Heat treatment processes, including quenching and tempering, enhanced the mechanical properties of steel. Quenching involved heating the steel to a high temperature and then rapidly cooling it, increasing its hardness. Tempering followed, reheating the steel to a lower temperature to reduce brittleness and improve toughness.

The shift towards plate armour also reflected changes in combat tactics and societal structures. As armour became more sophisticated and expensive, it reinforced the social hierarchy. Knights and nobles, who could afford the best armour, often served as heavy cavalry—the elite shock troops of medieval armies. The increased protection provided by plate armour allowed knights to engage more aggressively in combat. Heavy cavalry charges, supported by lances, became a dominant tactic.

However, the development of plate armour also spurred advancements in weaponry designed to counter it. Weapons such as the war hammer, mace, and pollaxe were engineered to deliver concussive force capable of denting or breaching plate armour. The estoc, a long, narrow sword, was designed for thrusting into the gaps between armour plates.

By the late 14th century, the full harness of plate armour, often referred to as 'white armour' due to its polished steel surface, had emerged. This armour covered nearly the entire body with interlocking plates, providing superior protection while maintaining mobility.

The transition from chainmail to plate armour was not uniform across Europe or even within England. Economic factors, regional styles, and individual preferences led to a variety of armour configurations. Some soldiers continued to use older styles or mixed elements due to availability and cost.

This period of transition illustrates the constant interplay between offensive and defensive technologies in medieval warfare. Armourers and warriors had to adapt continually to new threats, balancing protection, mobility, and practicality. The evolution of armour during the 13th and 14th centuries set the foundation for the advanced plate armours of the 15th century.

The Zenith of Armour Craftsmanship

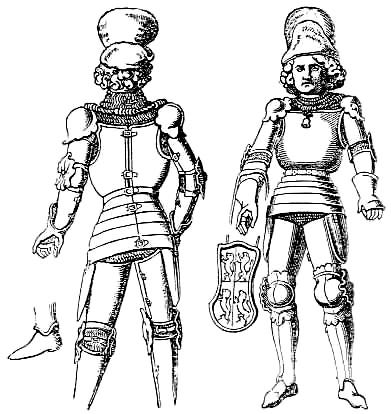

The 15th century is often considered the golden age of armour craftsmanship in England. During this time, armour reached a pinnacle of both functionality and artistic expression. English armourers, influenced by and contributing to broader European trends, produced full plate armours that were masterpieces of engineering and design.

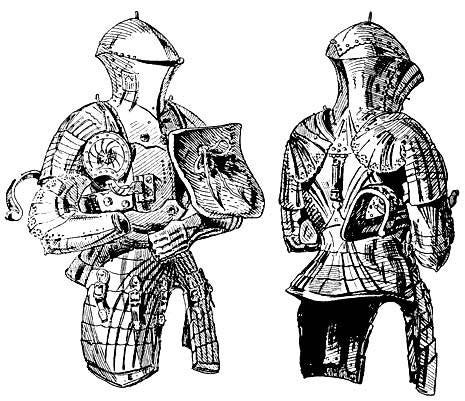

Creating a full suit of plate armour was a complex process requiring specialized skills and knowledge. Armourers, or 'platers,' worked with iron and steel to produce plates that were shaped, hardened, and fitted to the individual wearer. The process began with design and pattern making, where armourers took precise measurements and created patterns to ensure a perfect fit. This was essential for both protection and mobility.

Shaping the plates involved heating metal sheets and hammering them over forms or anvils to create the desired shapes. This process, known as 'raising,' allowed for complex curves and anatomical conformations. Heat treating was a vital step; armour plates were heated to specific temperatures and then quenched to achieve the desired hardness. Tempering reduced brittleness, ensuring the armour could withstand impacts without cracking.

Articulation was refined to an art, with overlapping plates connected by rivets and leathers, allowing for movement at the joints. Finishing the armour included polishing the surface to a high sheen and applying decorative techniques such as engraving, etching, gilding, and bluing to add aesthetic value.

The result was a suit of armour that provided comprehensive protection while allowing the knight to move relatively freely. Contrary to popular belief, full plate armour was not excessively heavy or cumbersome. A typical suit weighed between 45 to 55 pounds (20 to 25 kilograms), distributed evenly over the body.

The design of plate armour also reflected aesthetic sensibilities. Fluting and ridges were incorporated not only to strengthen the plates but also to create pleasing visual lines. Armour was often personalized with heraldic symbols, inscriptions, and motifs that reflected the owner's identity and values.

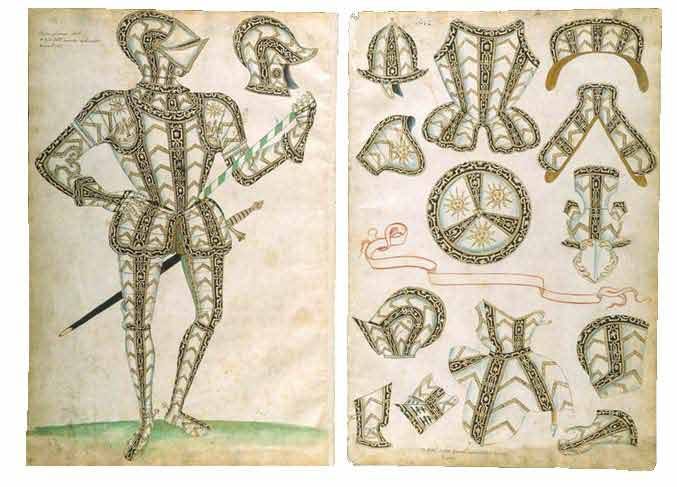

The establishment of the Royal Workshops at Greenwich under King Henry VIII in the early 16th century marked a significant development in English armour production. Although slightly beyond the medieval period, the Greenwich Armoury built upon the advancements of the previous century. The workshops attracted skilled armourers from across Europe, including Italy and Germany, leading to a fusion of styles and techniques. The armour produced combined English robustness with continental elegance.

Armour from Greenwich often featured the 'all'antica' style, inspired by classical antiquity, incorporating motifs like Roman gods, mythological creatures, and geometric patterns. Elaborate designs were etched onto the armour's surface and sometimes highlighted with gold leaf. Suits were customized to the individual, considering not only size but also intended use—battle, tournament, or ceremonial.

King Henry VIII was an avid collector and patron of armour. He commissioned numerous suits for different occasions, reflecting his interest in both martial prowess and display of wealth.

The zenith of armour craftsmanship represented a culmination of centuries of technological and artistic development. However, it also came at a time when the nature of warfare was changing. The increasing use of gunpowder weapons posed new challenges that even the finest plate armour struggled to meet.

Despite these emerging challenges, the armour of the 15th century remains a testament to the ingenuity and skill of medieval craftsmen. These suits are not only historical artifacts but also works of art that continue to captivate scholars and the public alike.

The Art and Science of Armoury

The production of armour was a multidisciplinary endeavor that combined art, science, and engineering. Armourers had to master metallurgy, mechanics, and aesthetics to create effective and visually appealing armour.

Metallurgy was at the heart of armour production. Understanding the properties of different metals was essential. Armourers selected materials based on factors like hardness, ductility, and resistance to corrosion. The transition from wrought iron to steel allowed for stronger and lighter armour. They experimented with various alloy compositions and heat treatment processes to enhance the performance of the steel.

Mechanical design was critical to ensure that the armour accommodated the human body's range of motion. This required precise engineering of joints and connections. Articulation points used sliding rivets, hinges, and leather straps to allow flexibility. Weight distribution was carefully considered, with armour designed to distribute weight evenly, reducing fatigue during prolonged wear.

Aesthetics played a significant role as well. Decorative elements were not merely ornamental but also conveyed social status, allegiance, and personal identity. Techniques like embossing—raising designs in relief—engraving, and damascening—inlaying different metals—enhanced the visual impact. Armourers incorporated motifs from classical antiquity, religious symbolism, and heraldic emblems.

The collaborative environment of workshops, especially prominent ones like Greenwich, fostered innovation. Armourers shared knowledge and experimented with new methods. They kept abreast of developments across Europe, incorporating and adapting foreign techniques. The influence of the Renaissance during the late medieval period introduced new artistic inspirations. Classical themes, symmetry, and proportion became more prevalent in armour design.

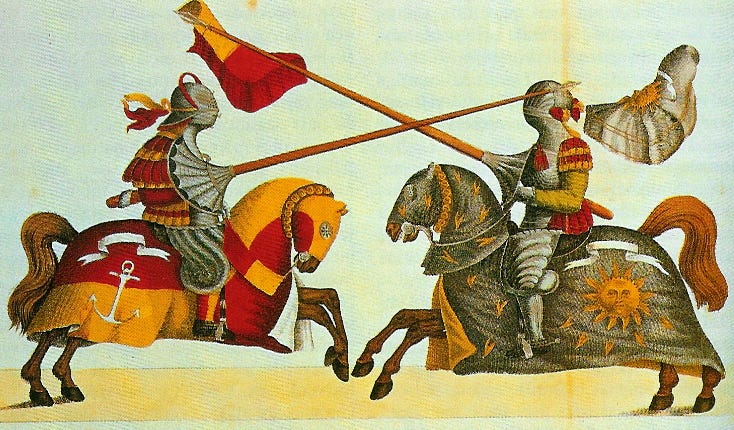

Armour served multiple purposes. Battle armour was designed for combat, prioritizing protection and functionality. Tournament armour was specialized for jousting and melee events, often heavier and more reinforced in specific areas to withstand impacts. Ceremonial armour emphasized aesthetics over practicality, used in parades and state occasions to display wealth and power.

Armour also played a role in diplomacy. Elaborate suits were commissioned as gifts to foreign dignitaries, symbolizing alliances and goodwill. These diplomatic armours were often some of the most ornate, showcasing the best of a nation's craftsmanship.

The decline of armour usage on the battlefield did not diminish its cultural significance. Armour continued to be an important symbol in heraldry, art, and literature. The skills developed by armourers influenced other crafts and industries, contributing to advances in metalworking and manufacturing.

The legacy of medieval armourers is evident in the meticulous craftsmanship that survives to this day. Their work represents a convergence of practicality and artistry that is a hallmark of the medieval period's technological achievements.

Helmets—The Knight's Signature

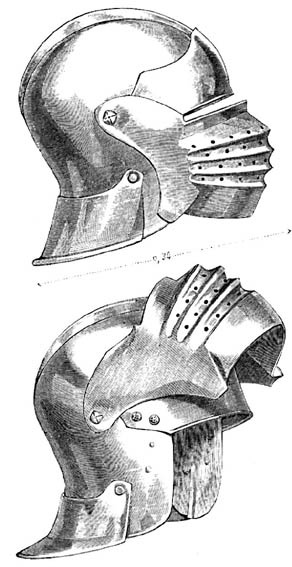

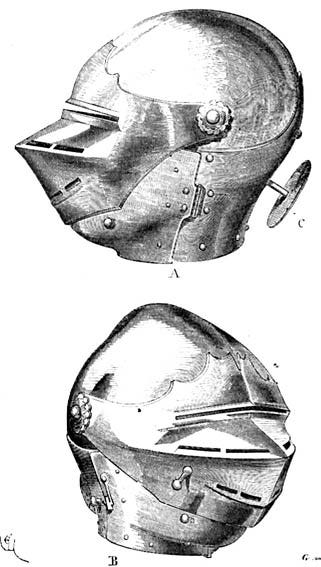

The helmet was a critical component of a knight's armour, providing essential protection for the head while also serving as a means of identification and expression. The evolution of helmets reflects the broader changes in armour design and the challenges faced on the battlefield.

Early helmets, such as the conical nasal helmets common among the Normans, had a simple design. They offered basic protection but left much of the face and neck exposed. As warfare evolved, the need for greater protection led to the development of more enclosing designs.

The great helm, emerging in the early 13th century, was a cylindrical helmet that enveloped the entire head. It had small eye slits and ventilation holes. While providing substantial protection, it restricted vision and airflow. The great helm was often used in conjunction with a smaller, lighter helmet underneath for added comfort and protection.

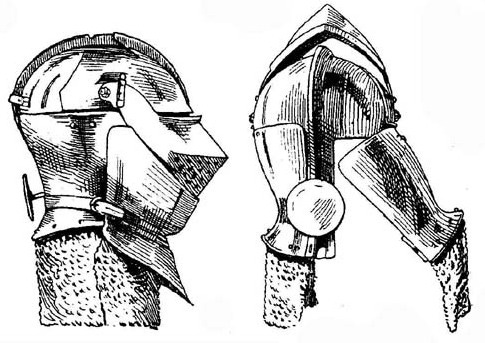

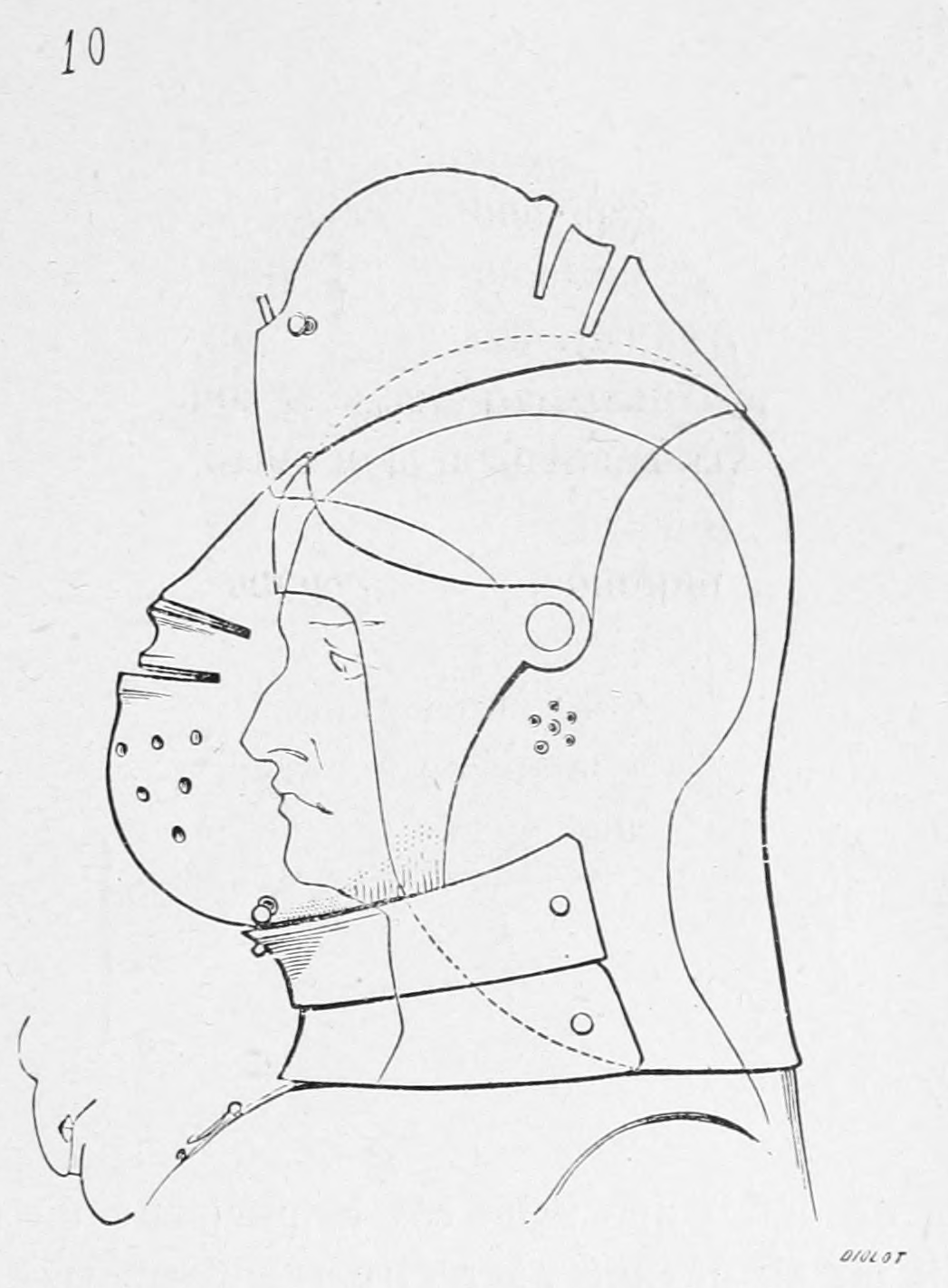

To address the limitations of the great helm, the bascinet was developed. This helmet featured a pointed or rounded skull cap and a movable visor. The addition of an aventail—a curtain of chainmail attached to the helmet's lower edge—protected the neck and shoulders. The visor could be raised or lowered, allowing the wearer to balance protection and visibility as needed.

As plate armour advanced, helmet designs continued to innovate. The sallet, popular in the 15th century, had a streamlined shape with an extended tail to protect the back of the neck. It often included a movable visor and was sometimes used with a bevor—a separate piece protecting the chin and throat. The armet represented a pinnacle in helmet design, characterized by fully enclosing the head with hinged cheek pieces and a visor. The armet provided comprehensive protection while maintaining a compact and ergonomic design.

Helmets were often richly decorated. Crests made from materials like wood, leather, or textiles were mounted on top and could depict animals, mythical creatures, or family emblems. These crests and decorative motifs served practical purposes in identification during battle and tournaments. They also conveyed the knight's lineage, achievements, and allegiances.

The design of helmets balanced the need for protection, visibility, and comfort. Innovations often emerged in response to specific threats or to improve upon previous designs. For example, the development of the visor addressed the need to protect the face without excessively compromising vision. The shape and construction of helmets also evolved to better deflect blows and projectiles.

Helmets were among the most personalized pieces of armour. The attention to detail and craftsmanship invested in helmets reflected their importance to the knight's identity and effectiveness in combat.

The study of medieval helmets provides valuable insights into the technological advancements and cultural values of the period. Their evolution illustrates the constant interplay between offensive and defensive measures in medieval warfare.

Armour on the Battlefield—Case Studies

Examining historical battles offers concrete examples of how armour functioned in real combat situations. Two significant battles that highlight the impact of armour are the Battle of Crécy in 1346 and the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

At the Battle of Crécy, the English army, led by King Edward III, faced a larger French force. The English utilized longbowmen effectively, positioning them on high ground with advantageous terrain. French knights, heavily armoured and mounted, charged repeatedly but were impeded by muddy ground and obstacles. The longbow arrows, with their high rate of fire and ability to penetrate armour at close ranges, caused significant casualties.

Similarly, at the Battle of Agincourt, King Henry V's English forces were outnumbered by the French. The battlefield was narrow and muddy due to recent rains. The French knights, though well-protected by their armour, were significantly hindered by the muddy terrain and the congested battlefield, which made coordinated movement difficult. While their armour provided essential protection, the environmental conditions and English tactics neutralized many of their advantages.

In both battles, armour provided essential protection but could not overcome strategic disadvantages and environmental factors. The effectiveness of armour was influenced by terrain, as muddy or uneven ground reduced mobility, especially under the weight of equipment. Tactics played a significant role; defensive positions and the use of ranged weapons could negate the advantages of armour. Additionally, the development of weapons specifically designed to counter armour, such as the longbow, challenged armour's protective capabilities.

These case studies demonstrate that while armour was a critical component of a knight's equipment, success in battle depended on a combination of factors. Commanders had to consider the strengths and limitations of their troops' armour in planning their strategies.

Understanding the role of armour on the battlefield provides a nuanced perspective on medieval warfare. It underscores the need for adaptability and the continuous evolution of military technology.

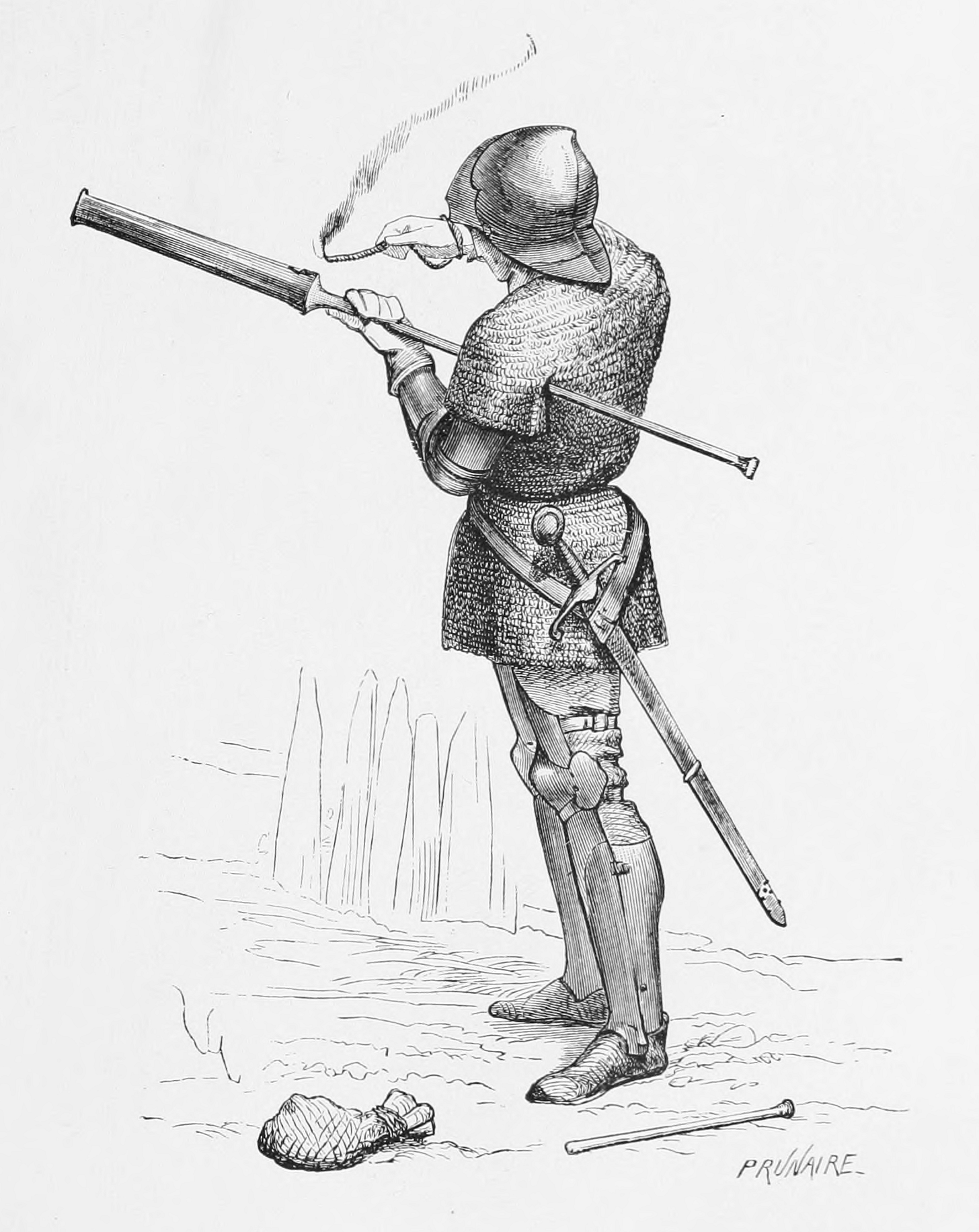

The Changing Face of Warfare

The late medieval period witnessed significant changes in warfare due to technological advancements. The introduction of gunpowder weapons, such as hand cannons and bombards, began to alter the dynamics of combat. Early firearms were primitive by modern standards—slow to reload, inaccurate, and unreliable. However, they possessed the ability to penetrate armour that had previously been impervious to traditional weapons.

Armourers responded by attempting to improve the protective qualities of armour. They experimented with thicker plates, increasing the thickness of armour to resist bullets, though this made armour heavier and less practical. They also enhanced steel hardness through improved heat-treating techniques and adjusted the shape and angles of armour to better deflect projectiles.

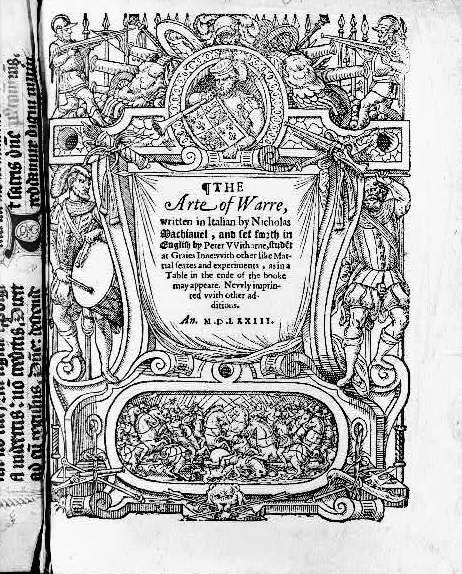

Despite these efforts, the effectiveness of armour against gunpowder weapons was limited. The increasing use of firearms among infantry and the development of artillery made traditional armour less viable on the battlefield. Military strategists recognized these shifts. Niccolò Machiavelli, in his work The Art of War, discussed how gunpowder weapons were changing the nature of warfare, diminishing the dominance of heavily armoured knights and emphasizing the importance of infantry and new tactics.

Armies began to reorganize, incorporating larger numbers of foot soldiers equipped with pikes and firearms. Cavalry roles shifted, and the emphasis on heavy armour declined. These changes did not happen overnight but marked the beginning of the end for traditional medieval armour on the battlefield. Armour continued to be used, particularly in ceremonial contexts, but its practical military role diminished.

The transition reflects the broader theme of technological innovation driving changes in military strategy and societal structures.

Armour in Society and Culture

Beyond its practical applications, armour held significant cultural and symbolic importance in medieval England. It was intertwined with concepts of knighthood, chivalry, and social identity.

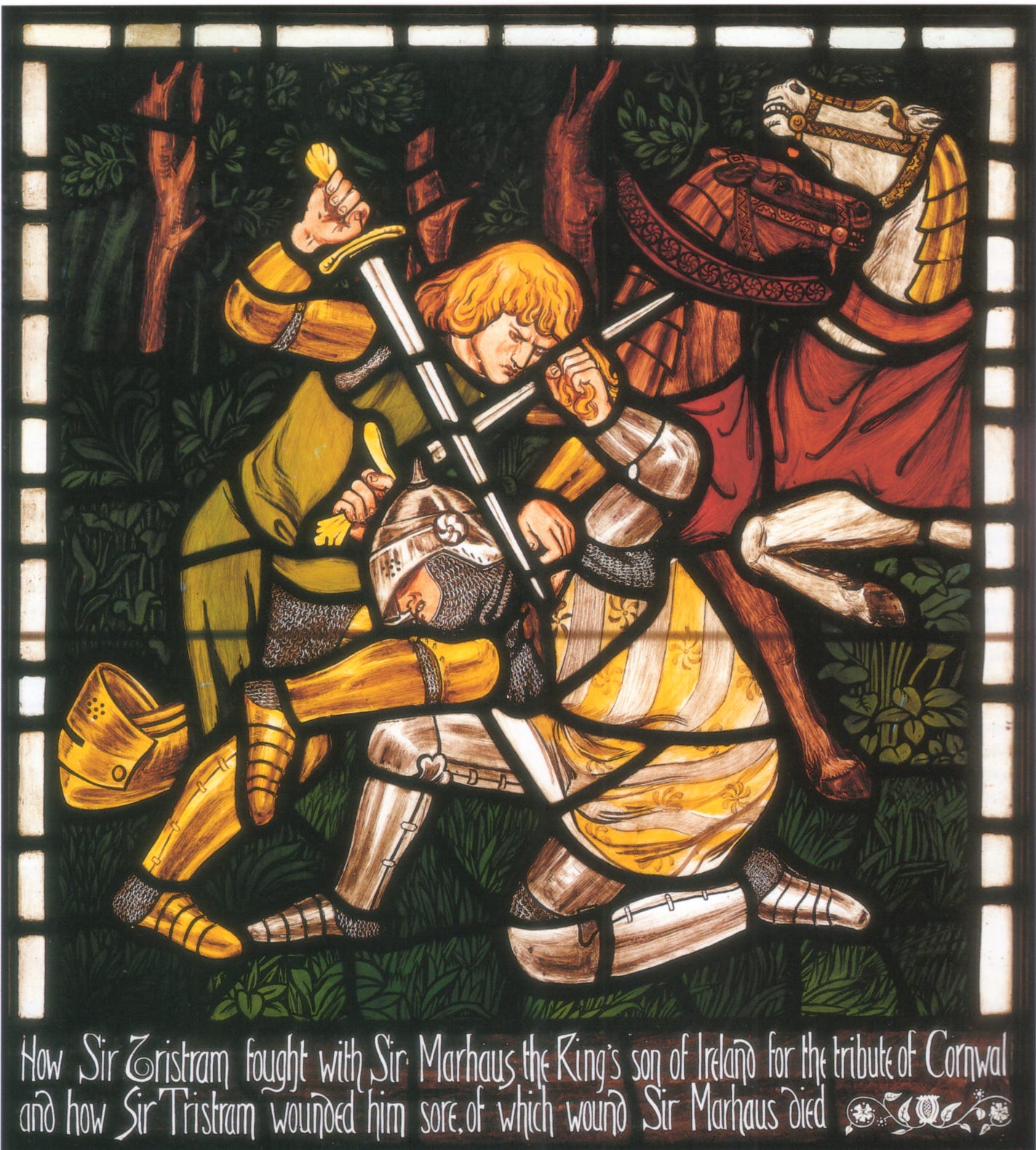

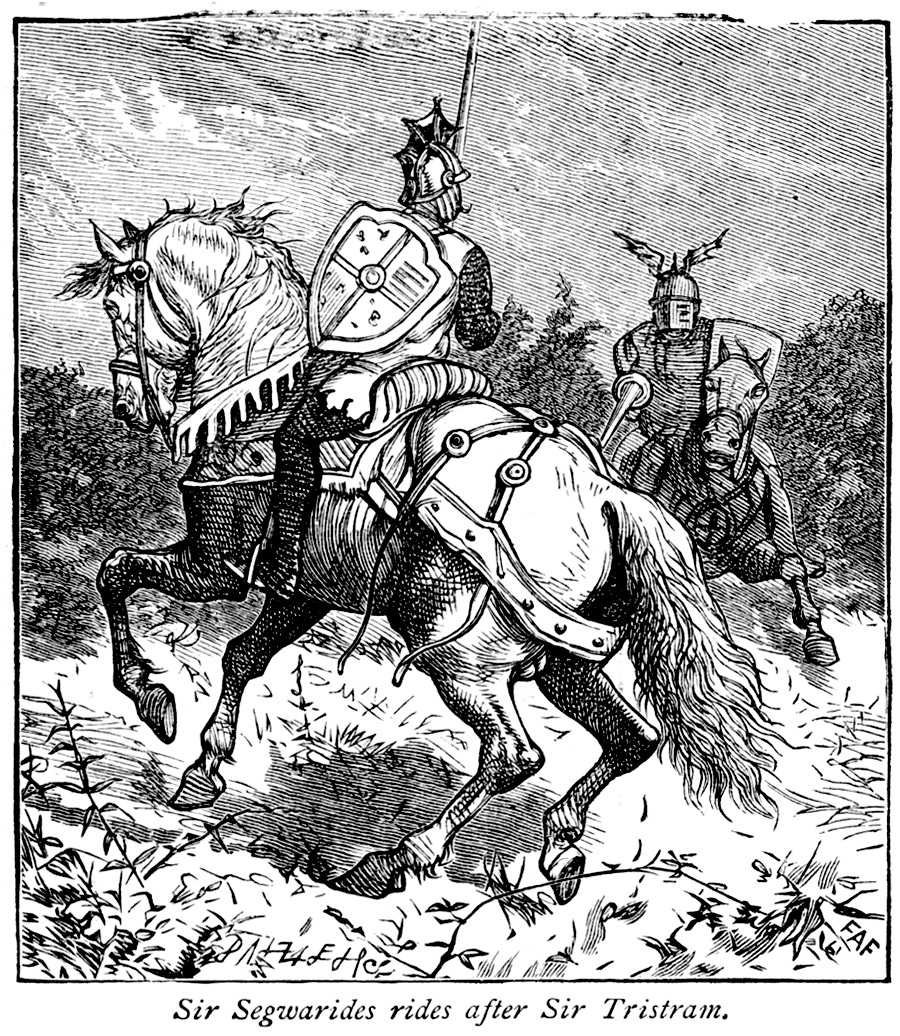

In literature and legend, armour featured prominently. Stories like Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur romanticized the ideals of knighthood. Armour symbolized the virtues of courage, honor, and service. Chivalric romances often depicted knights in shining armour embarking on adventures, reinforcing societal ideals.

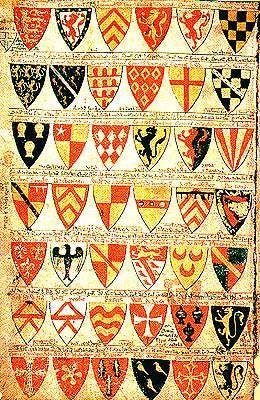

In art and heraldry, armour was prominently featured in paintings, sculptures, and stained glass. Artists paid meticulous attention to detail, reflecting the importance of armour in society. Heraldic symbols on armour and shields communicated lineage, alliances, and personal achievements.

Armour also played a significant role in ceremonial uses. It was worn during state occasions, parades, and tournaments. These events showcased martial skills and reinforced social hierarchies. Tournaments were not only sporting events but also opportunities for political maneuvering and displaying wealth.

Educational and moral symbolism saw armour used metaphorically in sermons and writings to represent spiritual protection and moral virtues.

The cultural significance of armour extended into the Renaissance and beyond. Even as its practical military use declined, armour remained a potent symbol in art and literature. The preservation of armour in collections and museums today allows us to connect with the values and aesthetics of the medieval period. It provides insights into the societal structures, artistic achievements, and historical narratives of the time.

The evolution of medieval armour in England is a story of innovation, adaptation, and expression. From the early chainmail hauberks introduced by the Normans to the sophisticated plate armours of the later medieval period, armour reflects the technological advancements and societal values of the times.

By exploring the development of armour, we gain insights into the lives of the knights who wore it—their roles on the battlefield, their place in society, and the cultural ideals they represented. The legacy of medieval armour endures, not only in museums and scholarly works but also in the collective consciousness. It continues to inspire fascination and serves as a tangible connection to a pivotal era in history.

Thank you for reading, if you enjoyed this article, please like, subscribe, and share for more articles covering medieval history.