Forging the Middle Ages: The Life and Craft of the Medieval Blacksmith

Amid the daily rhythms of medieval England, one artisan held a vital role in both rural hamlets and bustling towns—the blacksmith. Beyond the clang of hammer and anvil, the blacksmith was a master of metal whose craft shaped the tools of agriculture, the instruments of trade, and the weapons of war. Their skill in transforming raw iron into indispensable goods made them essential figures in a society built upon manual labor and craftsmanship.

In this article, we delve into the world of the medieval blacksmith. We'll uncover the origins of their craft, the crucial role they played in society, the intricate techniques they mastered, and the enduring legacy they left upon the fabric of history.

Origins

To fully appreciate the significance of the medieval blacksmith, we must journey back to the dawn of ironworking. Around 1200 BC, the advent of the Iron Age marked a transformative period in human history. The ability to extract iron from ore and forge it into tools and weapons revolutionized societies across Europe and beyond. In Britain, the Celts were among the first to practice ironworking, introducing their skills and traditions to the island's shores.

The Roman conquest of Britain in AD 43 brought new technologies and organizational methods. Roman blacksmiths, or fabri ferrarii, introduced advanced techniques, including improvements in smelting and forging processes. They established facilities to supply the Roman legions with weapons and tools, influencing local practices and setting foundations for future development.

With the decline of Roman rule in the early 5th century AD, Britain faced a period of social and technological change. However, the foundational knowledge of ironworking persisted, carried on by the Anglo-Saxons and later enriched by the Normans after 1066. The Normans introduced new administrative systems and continental influences that further shaped English blacksmithing practices.

By the High Middle Ages, spanning the 11th to 13th centuries AD, blacksmithing in England had evolved into a sophisticated craft. Iron became an indispensable versatile material used for a wide array of applications. Blacksmiths were the artisans of their time, transforming raw materials into essential goods that underpinned agriculture, warfare, construction, and daily life.

The Role of Blacksmiths in Medieval Society

The blacksmith was a linchpin of medieval communities, both rural and urban. His forge was not merely a workplace but a focal point of social and economic interaction. The services he provided were essential across all levels of society, bridging the gap between commoners and nobility.

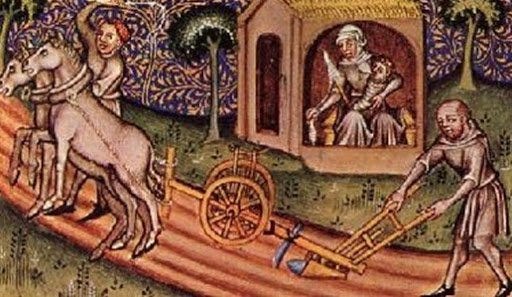

For the peasantry, who formed the majority of the population, the blacksmith's tools were vital for survival. Plowshares, hoes, scythes, sickles, and spades enabled them to till the soil, sow crops, and harvest food. Without these implements, agricultural productivity would have been severely limited, threatening food security and livelihoods. The blacksmith's ability to repair and maintain these tools extended their lifespan, conserving resources in a time when materials were precious and expensive.

Artisans and tradespeople also relied heavily on the blacksmith. Carpenters needed iron nails, saws, and chisels; masons required hammers and chisels capable of shaping stone; weavers used iron parts in their looms. The interconnectedness of crafts meant that the blacksmith's work supported a wide range of occupations, contributing to the overall economic vitality of the community.

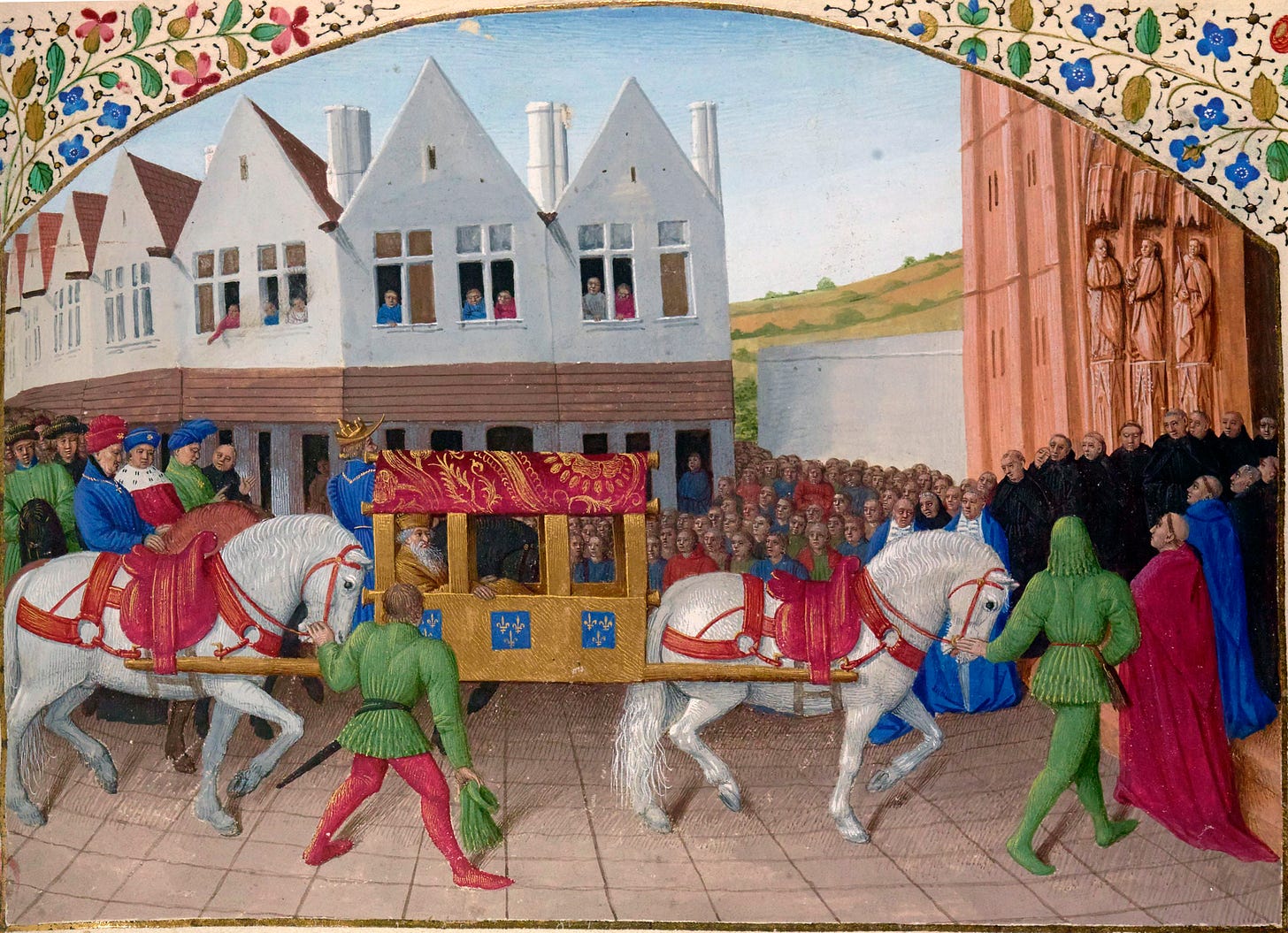

In the realm of transportation, the blacksmith's role was indispensable. Horses were the primary means of travel and labor, and the introduction of iron horseshoes in the 9th century AD marked a significant advancement. Horseshoes protected hooves from wear and injury, increasing the animals' endurance and utility. Blacksmiths also crafted metal components for carts, wagons, and carriages, facilitating trade and movement.

For the nobility and the emerging class of knights, the blacksmith's expertise was crucial in warfare. While specialized armorers and swordsmiths eventually developed, the local blacksmith often provided basic weaponry and armor. Spears, axes, daggers, and chainmail components were among the items forged. The blacksmith's work had a direct impact on a lord's military capabilities and, by extension, his power and influence.

The blacksmith's forge was more than a place of work; it was a social gathering spot. Villagers congregated there to exchange news, seek advice, and engage in communal activities. The blacksmith was often regarded with a mixture of respect and mystique, due to his mastery of fire and metal—a process that seemed almost magical to many.

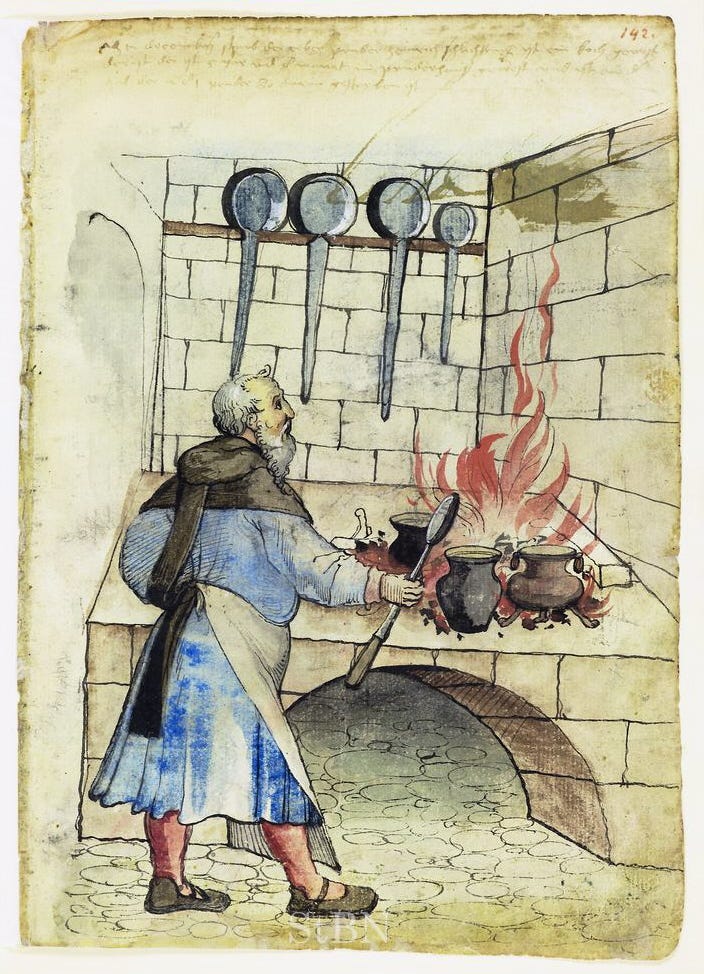

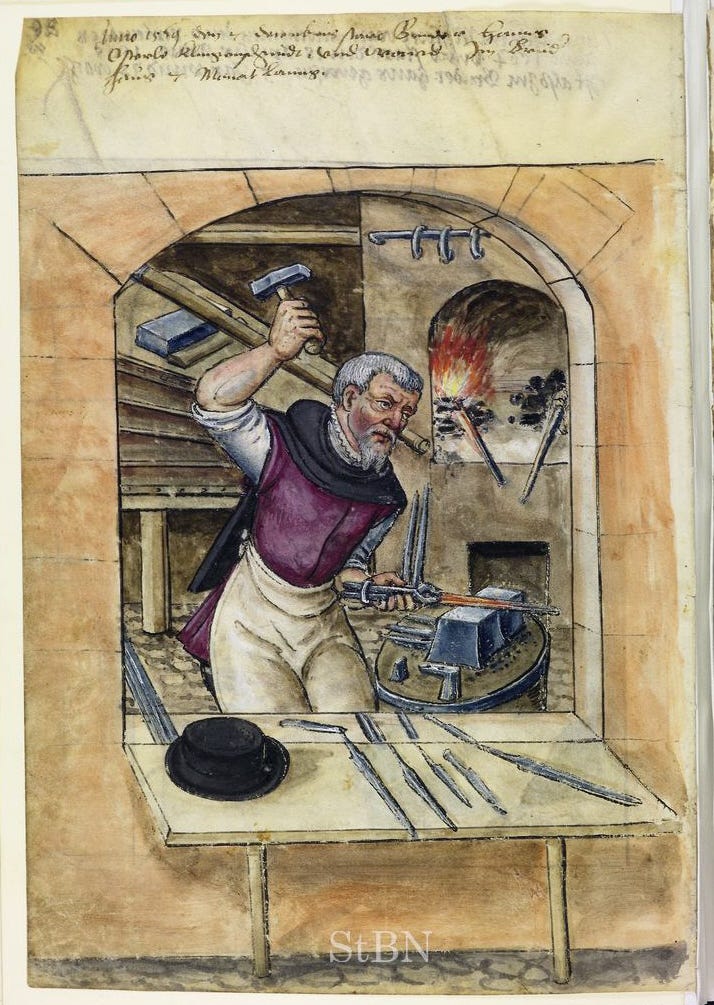

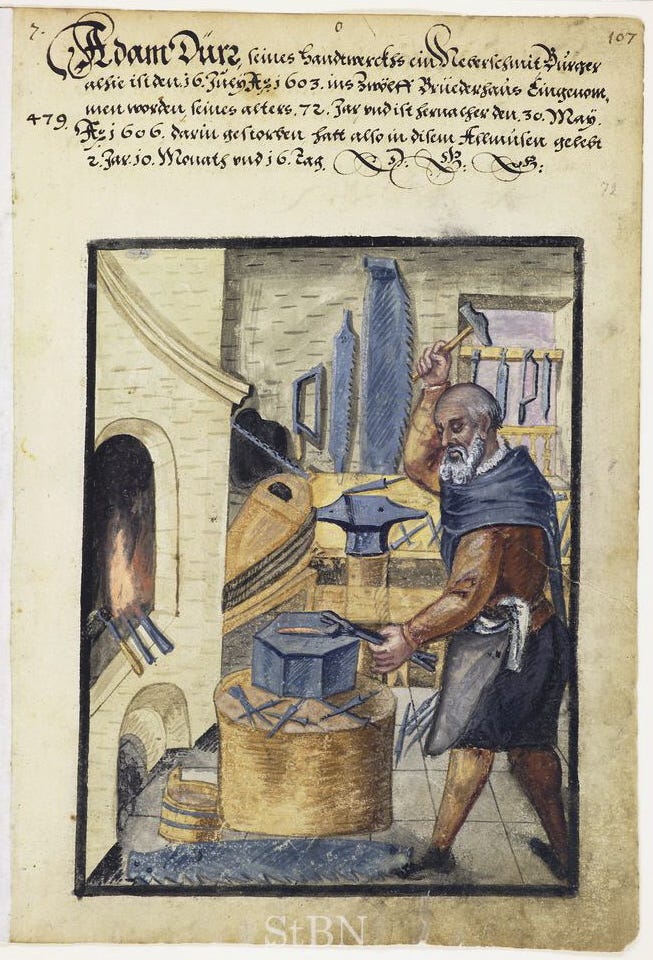

The Blacksmith's Workshop and Tools

The blacksmith's workshop was a realm where raw elements underwent transformative processes. Central to this environment was the hearth or forge—a specialized furnace where iron was heated to temperatures approaching 1,200 degrees Celsius. Achieving and maintaining such heat required skill and knowledge, as well as quality fuel. Charcoal was the primary choice, derived from hardwoods and carefully prepared to ensure consistent burning.

Bellows were essential for intensifying the fire. Operated by hand or foot, these devices injected air into the hearth, raising the temperature to the necessary levels for forging. In some regions and periods, larger forges employed water-powered bellows, integrating mechanical innovation into the craft.

The anvil was the blacksmith's principal workspace. Typically made of wrought iron with a hardened steel face, the anvil provided a resilient surface for shaping metal. Features like the horn allowed for bending and curving, while the hardy hole accommodated additional tools such as chisels and swages.

A vast array of hammers was employed, each serving a specific purpose. Sledgehammers delivered powerful blows for heavy work, while smaller hammers allowed for precise shaping and finishing. Tongs, essential for handling hot metal, came in numerous designs to grip various shapes and sizes securely.

Understanding the properties of different metals, controlling the temperature of the forge, and timing each step were critical components of the craft. Mistakes could result in flawed or weakened items, which could have serious consequences, especially in tools or weapons. The forge was often a multifunctional space. In addition to the main hearth, there might be secondary work areas for filing, finishing, or repairing items. Organization was key—the storage of raw materials and completed goods, as well as the maintenance of tools, required careful management. The blacksmith's workshop was a testament to the complexity and sophistication of medieval craftsmanship.

The Blacksmith's Materials and Techniques

The journey from raw iron ore to a functional object was intricate and required a deep understanding of materials and processes. Medieval blacksmiths typically worked with wrought iron, produced through the bloomery smelting method. This iron was characterized by its ductility and contained slag inclusions—remnants of the smelting process—that could affect its strength and workability.

Key techniques employed by blacksmiths included drawing out, which involved elongating the metal by hammering it along its length to thin and lengthen it for items like nails, blades, and rods. Upsetting thickened the metal by hammering it back onto itself, created heads on bolts or reinforce specific areas. Bending and twisting allowed the blacksmith to shape the metal into curves or spirals for decorative elements, hooks, and chain links. Forge welding joined two pieces of metal by heating them to a high temperature and hammering them together, requiring precise control to avoid burning the metal or creating weak joints.

Heat treatment processes were critical for altering the metal's properties. Hardening involved heating iron or steel to a high temperature and then rapidly cooling it in water or oil, increasing hardness but also making the metal brittle. Tempering followed, reheating the hardened metal to a lower temperature and allowing it to cool slowly, reducing brittleness while maintaining strength.

The blacksmith's ability to manipulate these properties allowed for the creation of tools and weapons tailored to specific functions. For example, a sword needed a hard edge for sharpness but a flexible spine to absorb impact—achieving this balance was a mark of exceptional skill. Materials used also included steel, an alloy of iron with a higher carbon content. Steel was more challenging to produce but offered superior hardness and strength. Techniques such as case hardening—infusing carbon into the surface of iron—allowed blacksmiths to create items with hard exteriors and tough cores.

Understanding the science behind these techniques, even if not in modern terms, was essential. Blacksmiths relied on visual cues, such as the color of heated metal, and tactile feedback to gauge temperatures and material properties. Their empirical knowledge, passed down through generations, formed the basis of metallurgical advancements.

Apprenticeship and Training

The path to becoming a blacksmith was demanding and required significant commitment from both the apprentice and his family. Apprenticeships were formal arrangements, often lasting seven years, during which the apprentice lived with the master and became part of his household. The apprenticeship contract outlined the duties and expectations of both parties. The apprentice agreed to obey the master, maintain confidentiality of trade secrets, and uphold moral conduct. In return, the master provided training, basic education, and necessities like food and lodging. Sometimes a fee was paid by the apprentice's family, reflecting the value placed on the opportunity.

Initial tasks were designed to instill discipline and familiarize the apprentice with the forge's environment. Responsibilities included maintaining the forge by cleaning the workspace, organizing tools, and ensuring supplies of charcoal and raw materials. Learning to operate the bellows was crucial, as it involved controlling the airflow and maintaining consistent temperatures. Assisting the master by holding tools, fetching items, and closely observing techniques was an integral part of the learning process.

As the apprentice gained experience, he began hands-on practice. Starting with basic items like nails and simple fittings, he honed his hammering techniques and developed an understanding of metal behavior. Mistakes were expected and served as learning opportunities, with the master providing correction and guidance.

In England, the progression from apprentice to independent craftsman did not always involve a formalized system requiring the production of a 'masterpiece,' as seen in some continental guilds. Upon completing the apprenticeship, the individual became a skilled craftsman, often referred to simply as a blacksmith. Achieving greater status could depend on factors like experience, reputation, wealth, and acceptance by peers within any local guild or community.

Blacksmiths and Guilds

Guilds were pivotal institutions in medieval towns and cities, and blacksmiths often formed their own or joined broader metalworking guilds. These organizations served multiple purposes: regulating trade, ensuring quality, protecting economic interests, and providing social support for members. In urban centers, guild membership offered numerous benefits. Exclusive permission to practice the craft within a certain area limited competition from non-guild members. Establishing guidelines for quality, pricing, and ethical conduct protected both craftsmen and consumers. Controlling apprenticeships maintained high levels of skill and consistency in training, and collective bargaining for materials and shared resources provided economic support.

However, in rural areas, many blacksmiths operated independently, serving their local communities without formal guild affiliation. This independence affected their economic interactions and allowed them to adapt more freely to the specific needs of their customers. Guilds wielded significant political influence in towns. They could lobby municipal authorities, participate in governance, and contribute to public works. Their wealth and organization made them powerful entities within the urban landscape.

Obligations came with membership. Guild fees, adherence to strict regulations, and participation in guild activities were mandatory. Violations could result in fines, suspension, or expulsion, which had severe economic consequences. Guilds also fulfilled social and religious roles. They organized festivals, sponsored religious services, and engaged in charitable works such as supporting hospitals and providing for the poor. This fostered a sense of community and reinforced social hierarchies.

The Blacksmith's Products—Tools, Weapons, and Everyday Items

The blacksmith's output was as diverse as it was essential. In agriculture, tools such as plowshares enabled deeper tillage of soil, improving crop yields. Harrows broke up clods, and hoes allowed for effective weeding. The durability and effectiveness of these tools directly influenced food production and the well-being of the population.

In construction, blacksmiths provided nails, hinges, locks, and structural components. The availability of reliable metal hardware facilitated the building of sturdier homes, bridges, and public buildings. Architectural ironwork also added aesthetic value, with decorative elements enhancing churches, castles, and manors.

Household items crafted by blacksmiths improved daily life. Pots, pans, kettles, and utensils made cooking more efficient. Iron candlesticks and lanterns extended productive hours into the evening. Tools for crafts—shears for wool, needles for sewing, and spinning wheel components—supported domestic industries.

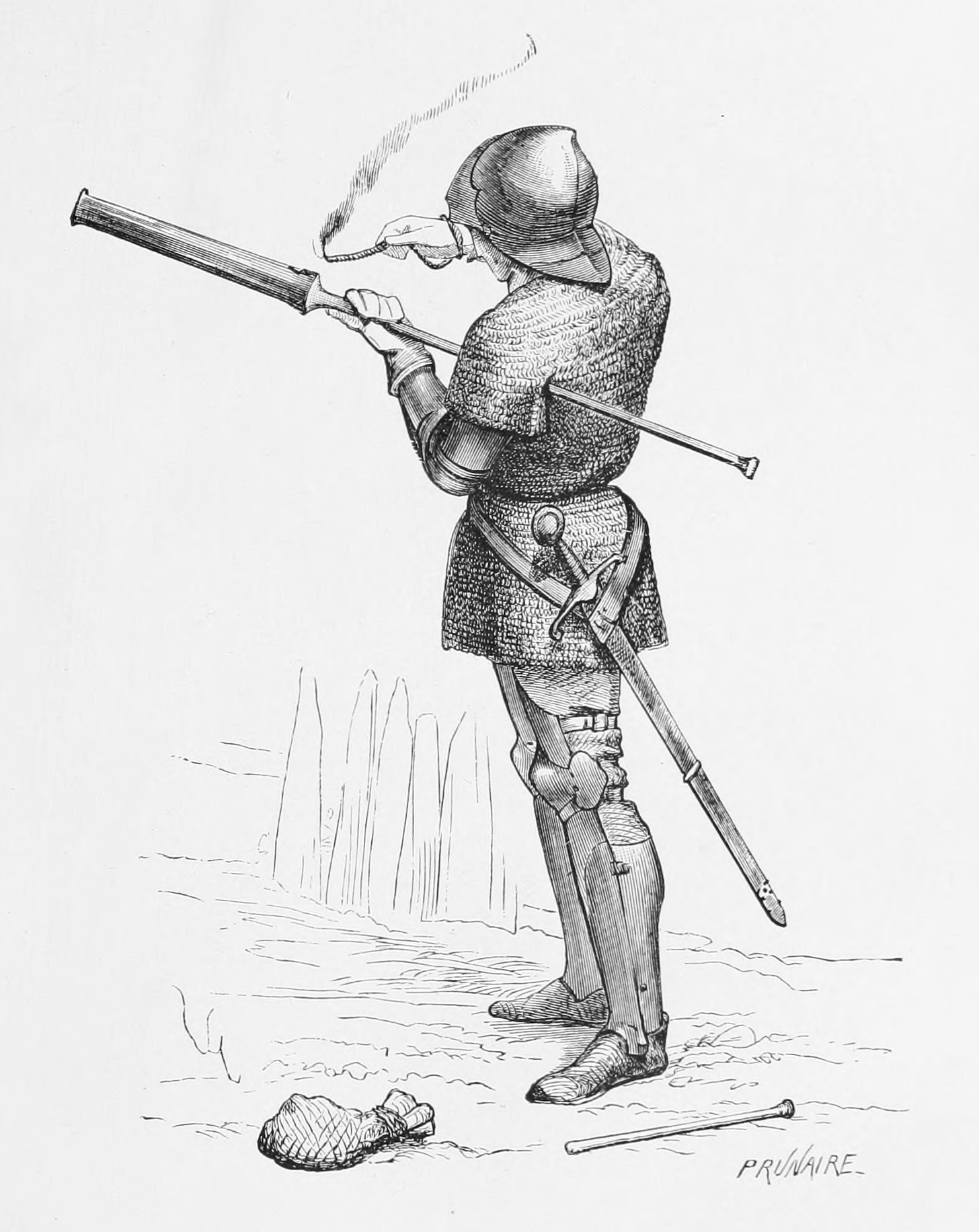

Weaponry was a significant aspect of the blacksmith's work. While specialized weapon makers emerged, many blacksmiths produced essential arms. Spears and pikes were common for foot soldiers, axes served both as tools and weapons, and arrowheads were in constant demand. The quality of these items could be a matter of life and death in conflict.

Blacksmiths also contributed to ecclesiastical needs. Ironwork adorned churches in the form of gates, screens, and fittings. Bells, though often cast by specialists, required iron components. The blacksmith's artistry in these projects reflected both skill and devotion.

Customization and adaptability were hallmarks of the blacksmith's craft. They often worked on commission, tailoring items to specific requirements. Repairs and maintenance formed a significant part of their business, extending the lifespan of valuable goods.

Blacksmiths and Warfare

Warfare was a pervasive aspect of medieval life, and the blacksmith's role in supporting military endeavors was crucial. The demands of war spurred advancements in metallurgy and weapon design. Blacksmiths were at the forefront of these developments, their expertise directly impacting a lord's military capabilities.

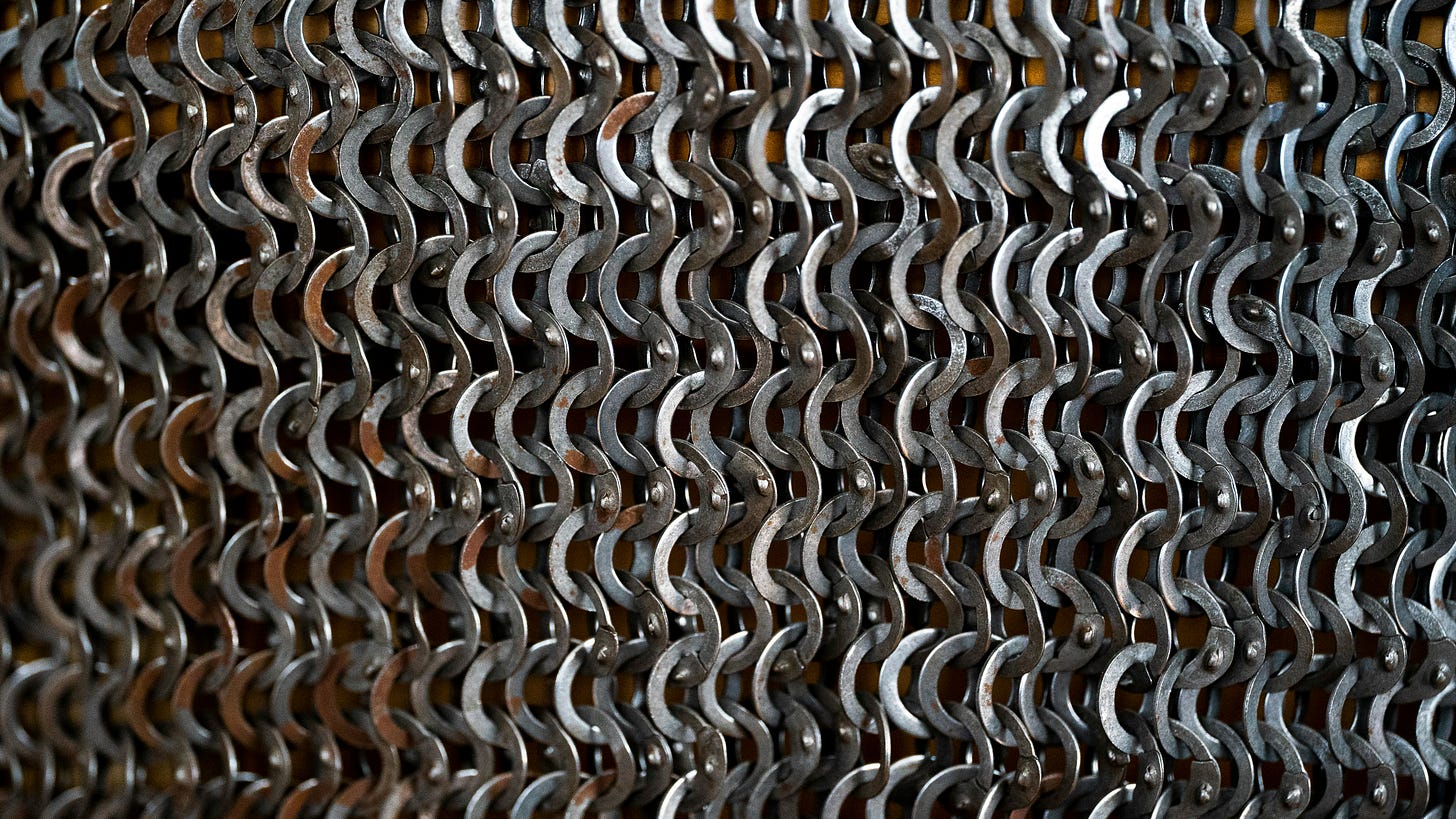

Chainmail, composed of thousands of interlocking iron rings, required meticulous craftsmanship. Each ring had to be forged, shaped, and riveted—a labor-intensive process that showcased the blacksmith's precision. Plate armor, emerging in the later medieval period, presented new challenges in shaping and hardening larger metal pieces.

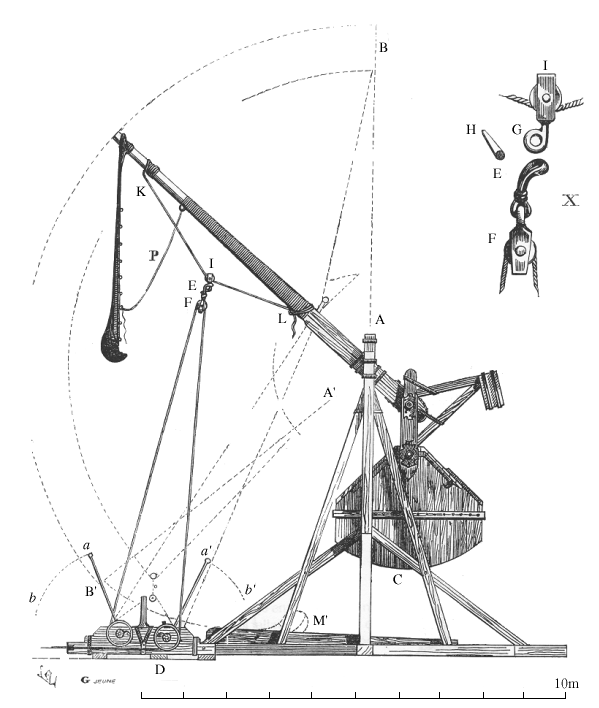

Weapons evolved in response to changing tactics and armor. Blacksmiths produced maces and war hammers designed to penetrate armor, as well as components for longbows and crossbows that revolutionized ranged combat. Siege engines, such as trebuchets and battering rams, incorporated metal parts that required the blacksmith's skill.

Logistics were vital in military campaigns. Blacksmiths accompanied armies, setting up mobile forges to repair equipment on the move. Their ability to maintain weapons, armor, and transportation was essential for operational readiness. Horseshoes needed constant replacement, and wagons required reinforcement—tasks that only a skilled blacksmith could perform under field conditions.

The blacksmith's contribution extended beyond physical goods. Their knowledge of metallurgy influenced the development of stronger and more resilient materials. Techniques for producing steel with higher carbon content led to superior weapons, giving armies a competitive edge.

The Social Status of Blacksmiths

The blacksmith's position in medieval society was multifaceted. On one hand, he was a skilled laborer, performing physically demanding and often dangerous work. On the other, he held a status that afforded respect and relative economic stability.

In rural settings, the blacksmith was among the more prosperous villagers. His services were essential, providing a steady demand for his work. Ownership of a forge and the ability to charge for services placed him above subsistence-level farmers and laborers.

In urban centers, blacksmiths could attain significant wealth, particularly those who specialized or engaged in trade. They might supply goods to merchants for export or produce luxury items for the affluent. Membership in guilds and associations connected them to influential networks, enhancing their social standing.

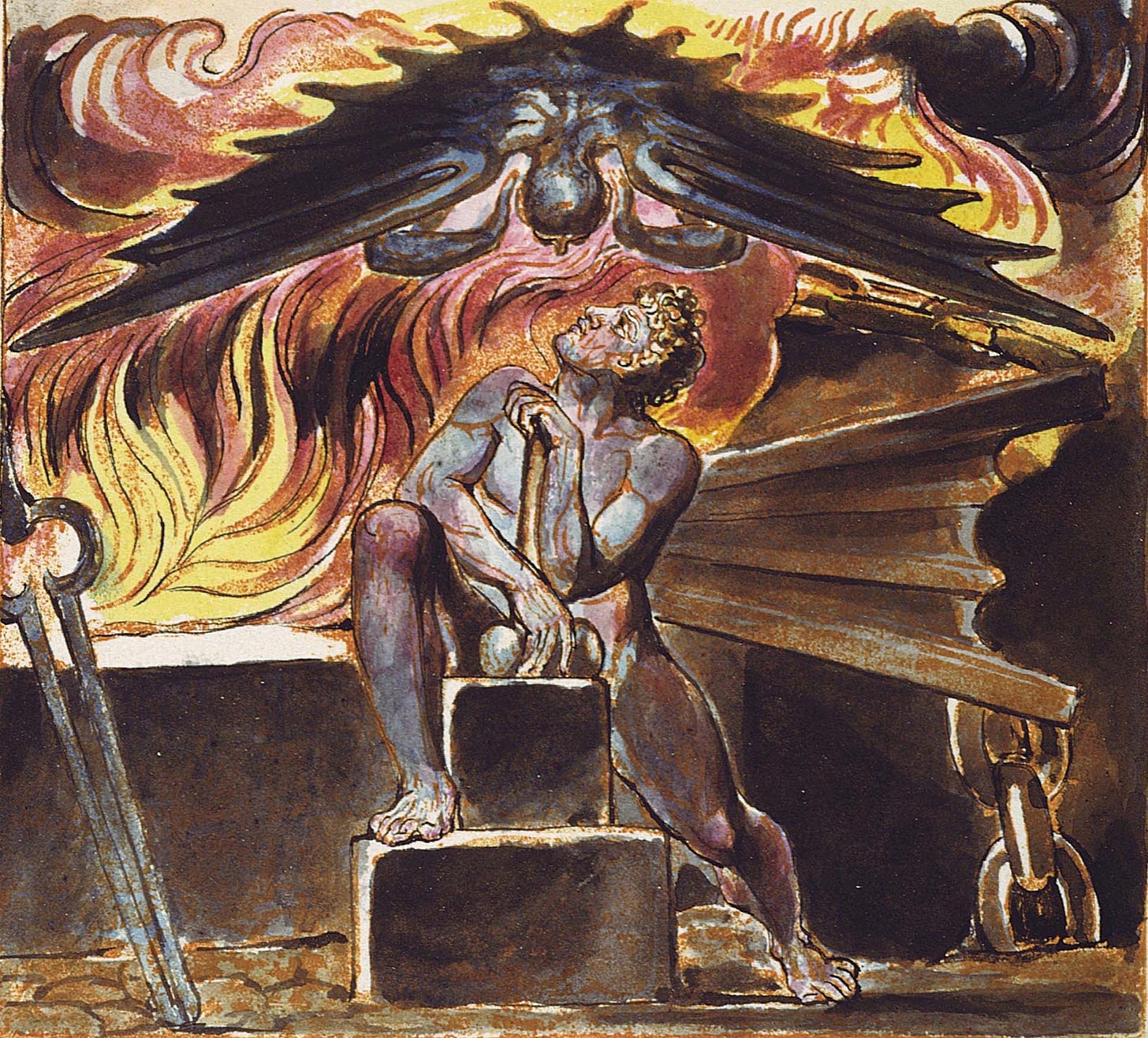

The blacksmith's expertise granted him a certain authority. His knowledge was unique, and his ability to manipulate metal—a mysterious and powerful element in the medieval mind—lent an air of mystique. Folklore and legends often portrayed blacksmiths as figures of wisdom or possessing special powers.

However, the profession was not without challenges. The physical demands were immense, leading to health issues such as respiratory problems from smoke inhalation and injuries from burns or repetitive strain. Economic fluctuations could impact material costs and demand for goods, affecting income stability.

Additionally, blacksmiths sometimes faced suspicion or jealousy. Their association with fire and transformation of materials bore a resemblance to alchemy or sorcery in the eyes of the superstitious. Navigating these perceptions required diplomacy and adherence to social norms.

Innovations

Innovation was a constant in the blacksmith's world. The quest for stronger, more durable, and more effective metal goods drove experimentation and adaptation. Techniques like pattern welding involved twisting and forging together iron and steel strips to create blades with decorative patterns and enhanced flexibility and strength. While visually striking, this method differed from the production of true Damascus steel, which originated in the Near East and involved unique crucible steel techniques not replicated in medieval Europe.

The introduction of waterpower transformed production capabilities. Water-powered hammers, or trip hammers, allowed blacksmiths to forge larger pieces and work more efficiently. This mechanization laid the groundwork for future industrial advancements and increased output.

Advancements in metallurgy, such as understanding the role of carbon in steel, led to improved materials. Blacksmiths learned to control carbon content through processes like carburization, tailoring the properties of metal for specific applications.

These technological strides had far-reaching impacts, contributing to economic growth, military power, and societal change. The blacksmith's role as an innovator highlights the dynamic nature of medieval craftsmanship and its influence on the progression toward modernity.

Challenges and the Evolution of the Blacksmith's Role

As the medieval period drew to a close, blacksmiths faced new challenges. The devastation of the Black Death in the 14th century AD reduced the population, leading to labor shortages and economic upheaval. Wages rose, and craftsmen found themselves in a changing economic landscape.

The advent of gunpowder weaponry began to change the nature of warfare, gradually reducing the demand for traditional forged weapons and armor. Blacksmiths had to adapt by learning new skills, such as repairing firearms and producing cannonballs.

Economic shifts, including the decline of feudalism and the rise of market economies, altered the dynamics of trade and labor. Some blacksmiths moved to urban centers where opportunities were greater, while others specialized in niche markets or higher-quality goods.

Technological advancements continued to influence the craft. The introduction of blast furnaces in Europe towards the end of the medieval period allowed for the production of cast iron in larger quantities. However, it wasn't until the early modern era that these furnaces significantly impacted ironworking practices. During the medieval period, the traditional bloomery furnace remained the primary method for smelting iron.

While industrialization and mass production would later challenge traditional blacksmithing, these developments occurred after the medieval period. In the late Middle Ages, blacksmiths remained integral to their communities, but their role was evolving in response to societal changes.

The Legacy of Medieval Blacksmiths

The legacy of medieval blacksmiths endures in various forms. Today's blacksmiths, though fewer in number, continue to practice and preserve the techniques developed over centuries. Their work is celebrated in artistic communities, educational programs, and heritage preservation efforts.

Museums and historical sites offer glimpses into the blacksmith's world, allowing us to connect with the past. Demonstrations and workshops engage new generations, fostering appreciation for the skill and artistry involved.

In literature and mythology, the blacksmith remains a potent symbol. From Wayland the Smith in Anglo-Saxon lore to representations in modern fantasy, the figure embodies creativity, transformation, and mastery over elemental forces.

The principles of metallurgy established by medieval blacksmiths underpin modern engineering and materials science. Their empirical knowledge contributed to the scientific understanding of metal properties and processing.

The blacksmith's influence extends to cultural values—emphasizing craftsmanship, dedication, and the importance of skilled labor. Their story reflects broader themes of technological advancement, societal change, and the human capacity for innovation.

The story of the medieval blacksmith is a testament to human ingenuity and the profound impact of skilled craftsmanship on society. From shaping tools that fed nations to forging weapons that altered histories, blacksmiths were architects of change.

Their legacy is intertwined into the very structures that define our modern world—visible in the steel frameworks of our cities, the technological advancements that drive progress, and the enduring appreciation for the art of metalworking.

By exploring their lives and contributions, we gain insight into the complexities of medieval society and the foundations upon which our present stands. The blacksmiths of the Middle Ages not only transformed iron but also forged a path toward the future.

Thank you for reading, if you enjoyed this article, please, like, subscribe, and share for more articles on medieval history.