The Origins of Knighthood in England

Knighthood—the very embodiment of medieval chivalry, martial prowess, and noble virtue. The image of a knight in shining armor has captured imaginations for centuries. But how did this institution originate? What historical forces gave rise to the English knight, and how did knighthood become such a defining feature of medieval English society? In this article, we delve deep into the roots of knighthood in England, tracing its emergence from the Early Middle Ages through the transformative events of the Norman Conquest and beyond. Join us as we uncover the societal, military, and cultural developments that forged the iconic figure of the English knight.

Early Medieval Warfare and Society

To understand the origins of knighthood in England, we must first explore the landscape of early medieval Europe. Following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, Europe entered a period of significant upheaval and transformation. This era, now commonly referred to as the Early Middle Ages, saw the formation of new kingdoms and the foundations of medieval European society. Tribal kingdoms rose and fell, and warfare was characterized by localized conflicts among competing warlords.

In Anglo-Saxon England, which emerged after the departure of the Romans, society was organized around kinship groups and tribal affiliations. The ruling elite were known as 'thegns,' warriors granted land by the king in exchange for military service. These thegns formed the backbone of the Anglo-Saxon military system.

Warfare during this period was primarily infantry-based, with soldiers forming shield walls—a tactic where warriors stood shoulder to shoulder, shields overlapping for protection. Although horses were used mainly for transportation, there is evidence that Anglo-Saxons employed cavalry in combat roles to some extent. For instance, accounts of the Battle of Maldon in 991 AD suggest the presence of mounted troops. However, cavalry did not have the tactical significance it would later assume under Norman influence, lacking the organization and impact of Norman heavy cavalry.

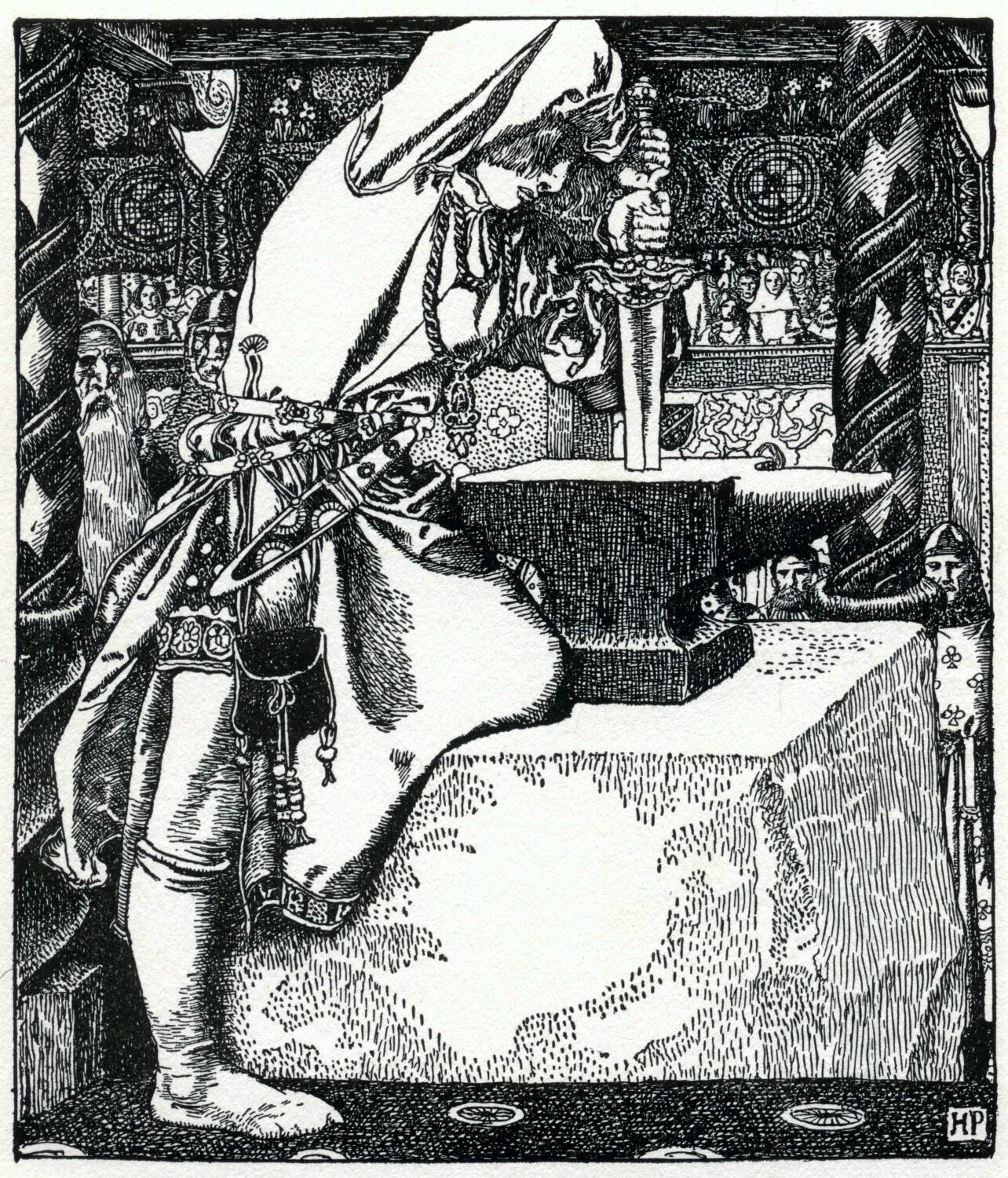

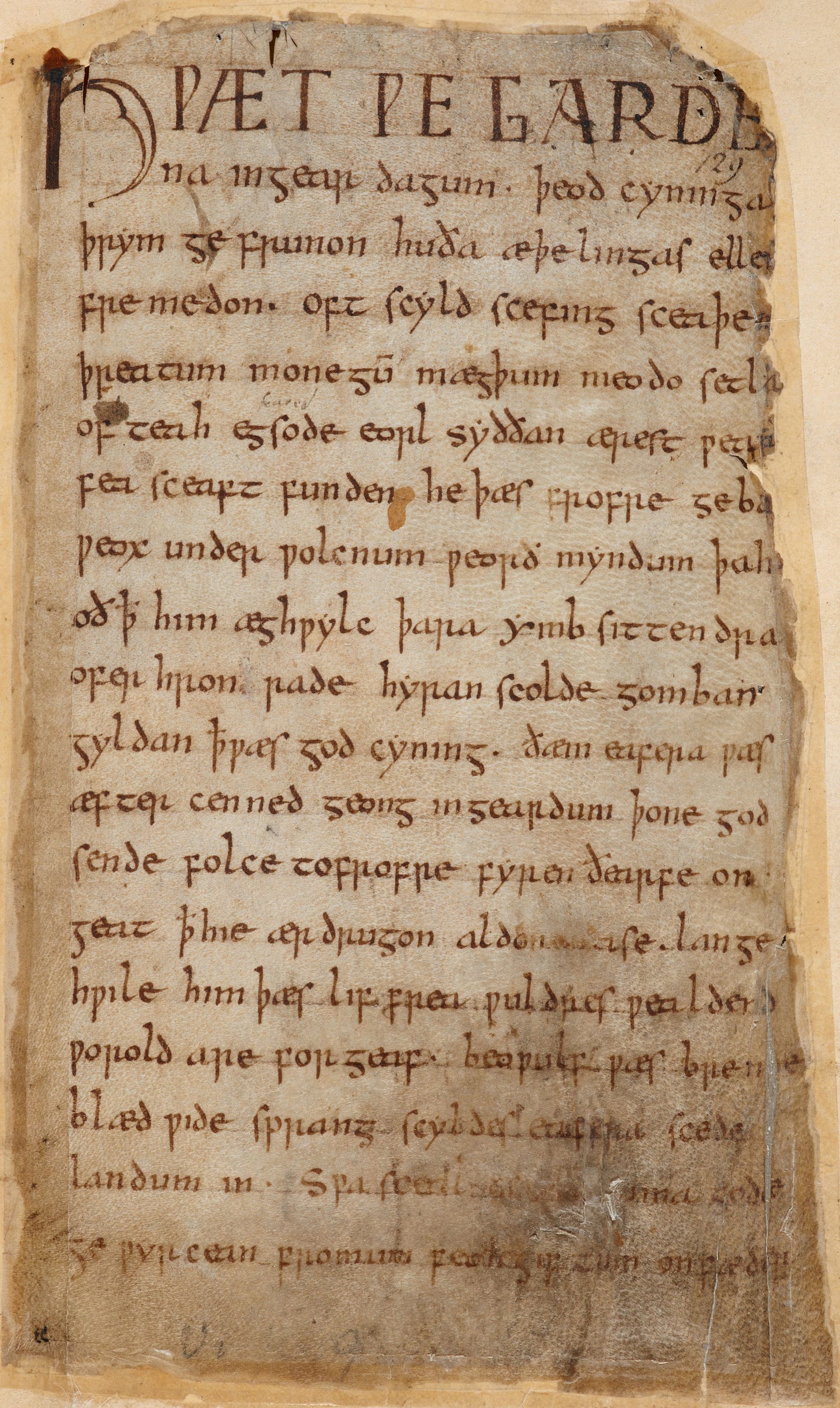

Heroic literature like 'Beowulf' depicts this warrior culture, emphasizing personal valor and loyalty to one's lord. The emphasis on individual bravery and the collective strength of the shield wall defined Anglo-Saxon military ethos.

The Norman Conquest and the Introduction of Feudalism

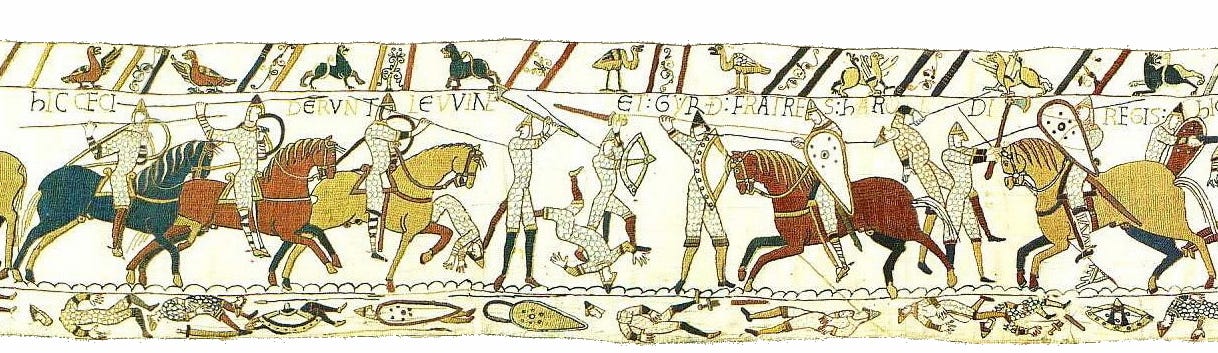

The pivotal moment in the origins of English knighthood came in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. William, Duke of Normandy, laid claim to the English throne and invaded England, culminating in the decisive Battle of Hastings. The Norman victory not only altered the ruling dynasty but also introduced profound changes to English society, governance, and military organization.

William the Conqueror brought with him a hierarchical system often described as 'feudalism'—a term coined by later historians to conceptualize the complex social and economic relationships of the time. It's important to recognize that medieval societies were intricate, and the nature of lord-vassal relationships varied across regions and periods.

At the apex of this system sat the king, who granted vast tracts of land to his most trusted nobles, known as barons. In return, these barons supplied knights to serve in the king's army. This new system fundamentally changed land ownership and social structures in England. The dispossession of many Anglo-Saxon nobles and the redistribution of land to Norman lords laid the groundwork for a new social hierarchy centered around the knightly class.

The Emergence of the Knightly Class

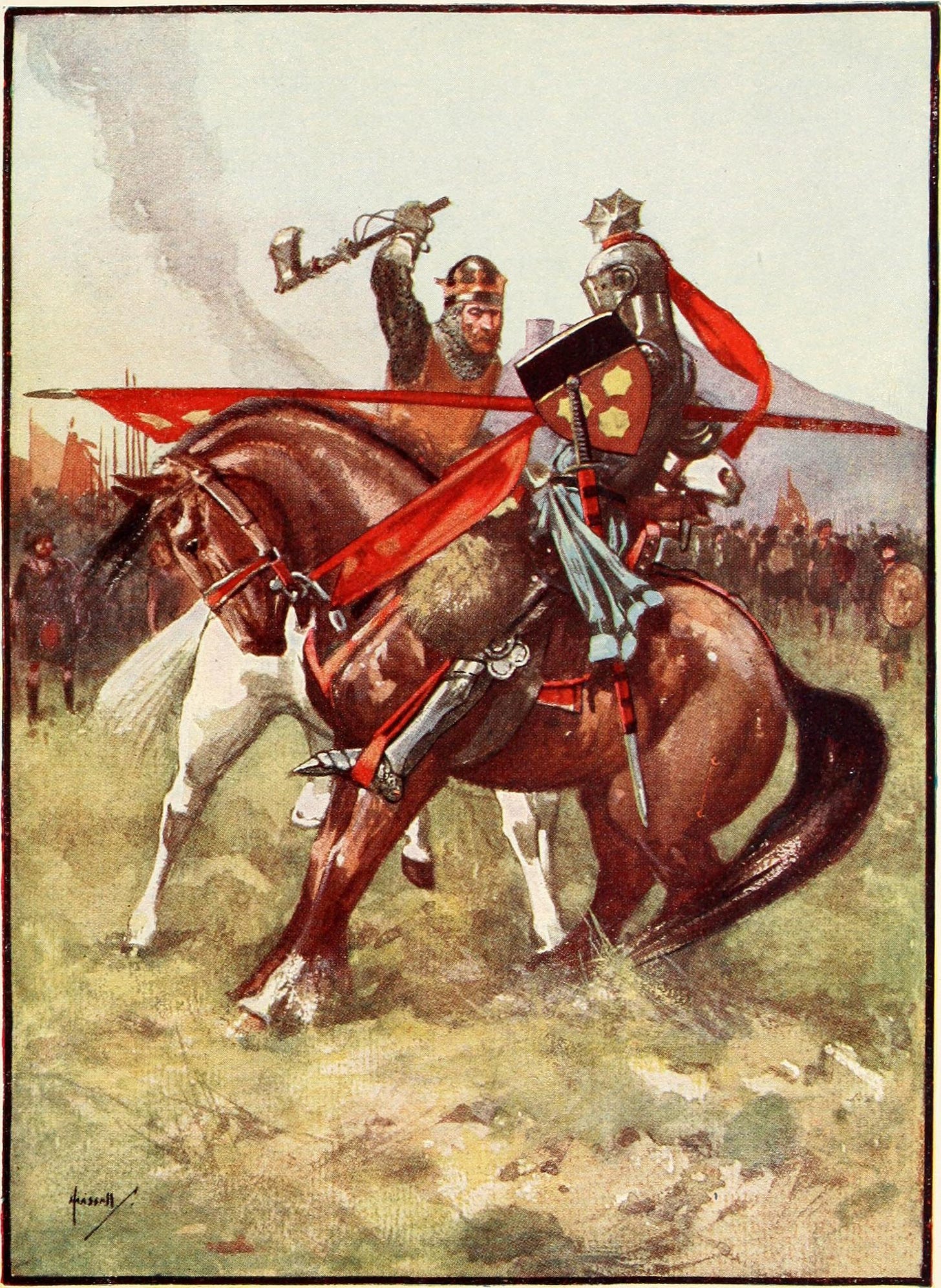

Central to Norman military success was the use of heavy cavalry—mounted warriors who fought with lances, swords, and shields. The Normans introduced advanced cavalry tactics to England, most notably the use of the couched lance, where the lance is held under the arm to deliver a powerful charge.

The word 'knight' derives from the Old English 'cniht,' meaning 'boy' or 'servant,' reflecting a young male attendant or apprentice. As social and military structures evolved, 'cniht' came to signify a mounted warrior of noble status in Middle English, mirroring the French term 'chevalier,' derived from 'cheval,' meaning horse.

Knights were heavily armored, wearing chainmail hauberks, conical helmets with nasal guards, and carrying kite-shaped shields. Their equipment was expensive, requiring significant resources to obtain and maintain. As a result, knighthood was closely tied to wealth and land ownership.

Knights were granted land holdings, known as 'fiefs,' by their lords in exchange for military service. This land provided the economic means to support their status and obligations. Thus, the knight became both a warrior and a landholder, embedded within the feudal hierarchy that defined medieval English society.

Military Innovations and Tactics

The introduction of the mounted knight transformed the nature of warfare in England. The mobility and shock power of cavalry charges could decisively break enemy formations. Knights often fought in tightly organized units called 'conrois,' coordinated by signals and banners.

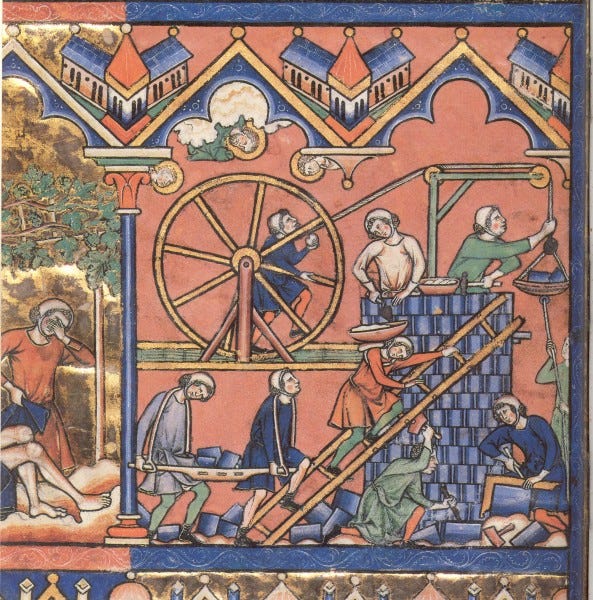

Castles were significantly developed and proliferated under Norman rule. While fortified structures like burhs existed in Anglo-Saxon England, the Normans introduced new designs, such as the motte-and-bailey castles, and built them extensively across the country. The rapid construction of these castles not only facilitated military control but also had profound effects on the local populace. Many castles were built on sites of existing communities, leading to displacement. These castles served as fortified residences, military bases, and imposing symbols of Norman authority over the Anglo-Saxon population.

These military innovations necessitated a professional warrior class trained in both offensive and defensive operations. The knightly class fulfilled this role, becoming indispensable to the medieval military system.

Cultural and Social Integration

As Norman and Anglo-Saxon societies began to merge, so too did their cultures and social structures. Many Anglo-Saxon thegns lost their lands and status following the Norman Conquest. However, some adapted to the new Norman-dominated hierarchy, and over generations, their descendants integrated into the emerging knightly class, blending Anglo-Saxon and Norman traditions.

The adoption of chivalric ideals evolved over the 12th and 13th centuries. The Church played a significant role in promoting these ideals, advocating for knights to uphold Christian virtues and protect the weak. Literature, such as the works of Chrétien de Troyes, popularized chivalric themes, blending martial valor with courtly love and spiritual quests. These influences elevated knighthood beyond mere military function to a comprehensive moral and social code that dictated a knight's behavior both on and off the battlefield.

Literature and poetry, such as the tales of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, reflected and reinforced these ideals. Although the historical Arthur predates the Norman Conquest, these stories became popular in the 12th and 13th centuries, blending myth with chivalric values.

The Expansion of Knighthood

During the 12th and 13th centuries, knighthood expanded both in numbers and influence. The growth of knightly families, the establishment of hereditary titles, and the practice of primogeniture—where the eldest son inherits the estate—contributed to the stability and continuity of the knightly class.

While knighthood remained predominantly the domain of the nobility, the ranks began to include lesser nobles and landholders. By the late medieval period, the expansion of commerce and the rise of wealthy urban elites allowed some non-noble individuals to achieve knighthood. Successful merchants or administrators who amassed wealth and land could sometimes be granted knighthood as a reward for services to the crown or through marriage into noble families. This blurring of social boundaries indicated a gradual shift in the rigid class structures of earlier periods.

Knights played an increasingly prominent role in local governance and administration. They served as sheriffs, justices of the peace, and held other official positions. Notable figures like Sir Geoffrey de Mandeville, who was appointed Sheriff of London, and Sir William Marshal, who served as regent and advisor, demonstrate the significant political influence knights could wield. Their participation in local courts and commissions contributed to the development of English common law and the administrative structures that would underpin the English legal system.

The Crusades and International Influence

The launching of the First Crusade in 1096 had a profound impact on knighthood in England. Many English knights joined these religious expeditions to the Holy Land, motivated by piety, the promise of spiritual reward, and the allure of wealth and land.

The Crusades exposed English knights to broader European chivalric culture and military practices. Encounters with knights from other regions facilitated the exchange of ideas, tactics, and innovations. Interaction with Eastern cultures and other European knights led to the exchange of not only military tactics but also artistic, architectural, and intellectual ideas. These influences enriched English culture and contributed to the cosmopolitan aspects of chivalric tradition.

The formation of military orders like the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller introduced new dimensions to the concept of knighthood. These orders exemplified a fusion of monastic life and military duty, emphasizing discipline, piety, and communal living. English knights who joined or interacted with these orders brought back ideals of religious dedication and organizational structure, which influenced secular knighthood in England.

Legal and Economic Aspects

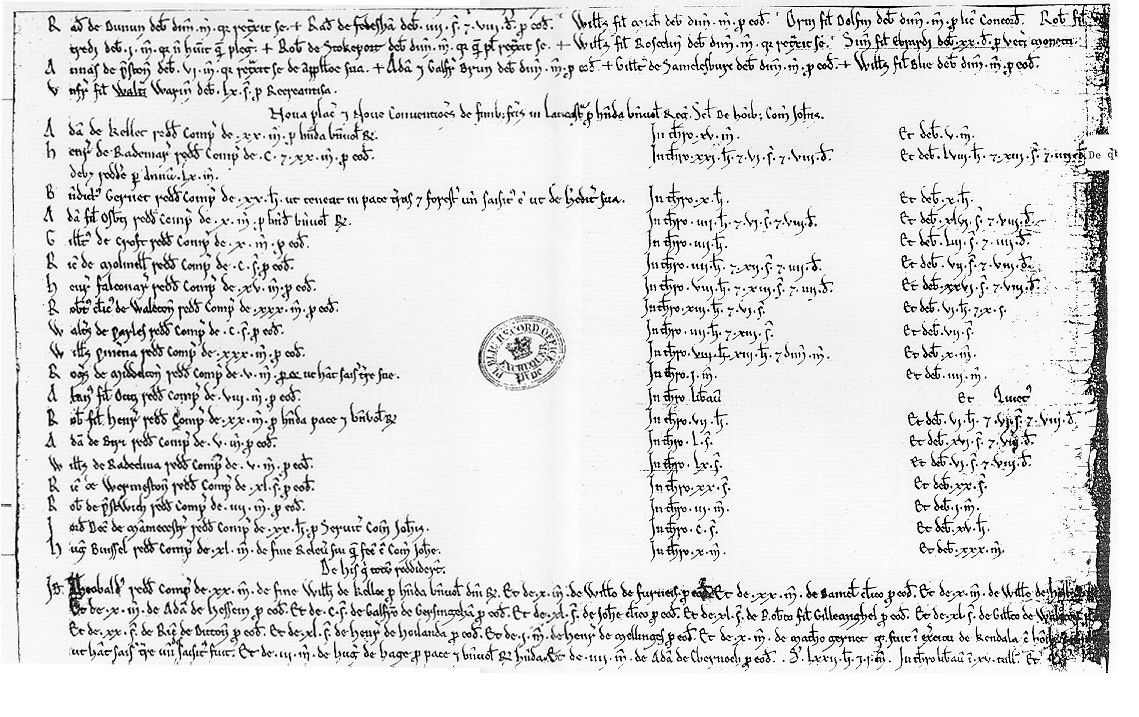

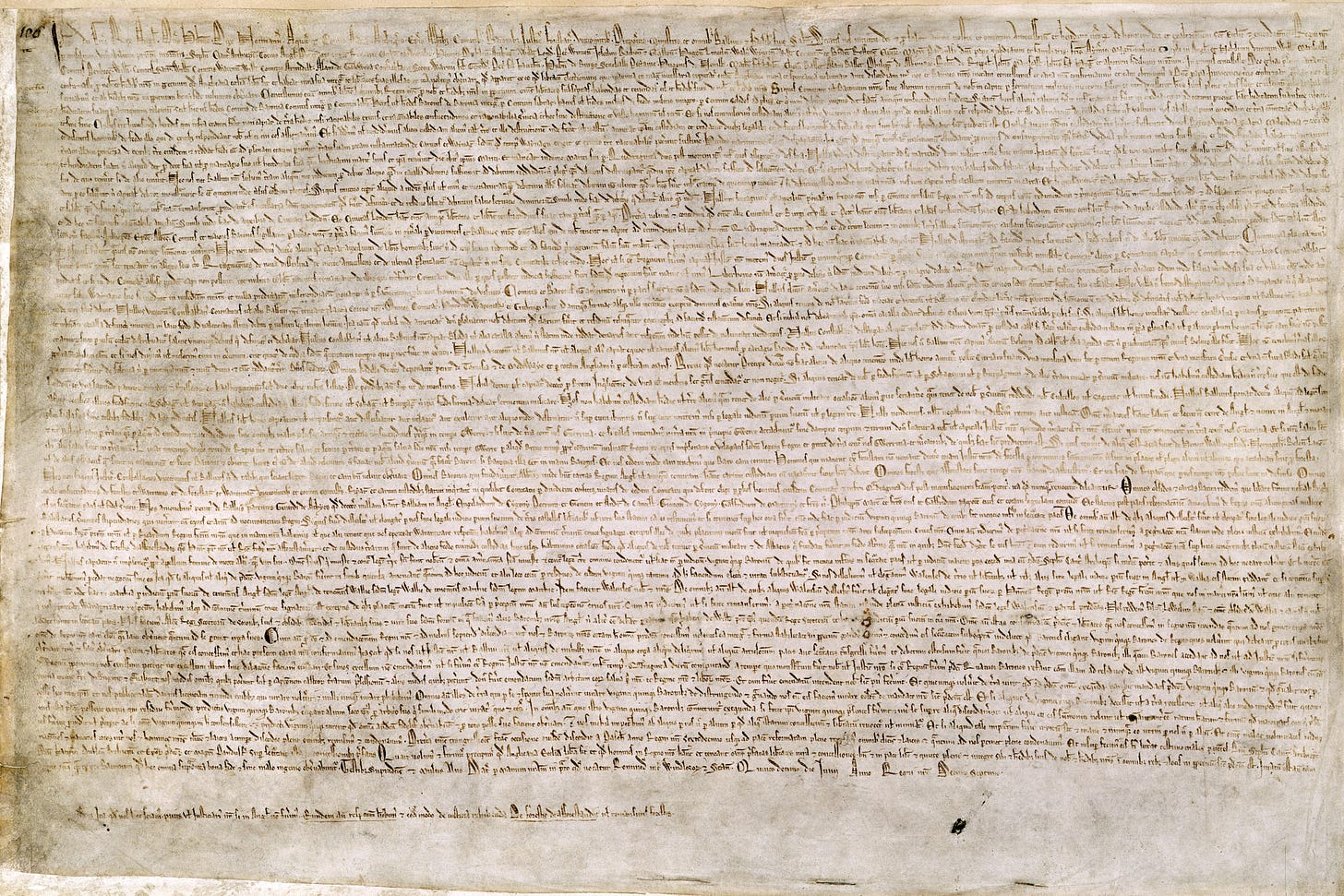

The legal framework of feudal obligations was formalized through documents like the Magna Carta in 1215. While primarily a response to the abuses of King John, the Magna Carta addressed the rights and duties of nobles and knights, including matters of inheritance, wardship, and the limits of royal authority.

Knights were subject to 'knight's fees,' a form of taxation based on their landholdings. They were obligated to provide military service for a specified period, typically 40 days per year. However, as warfare became more protracted and professionalized, this system evolved.

The practice of 'scutage' emerged, allowing knights to pay a fee instead of performing military service. The rise of scutage reflected the monarchy's shifting needs, favoring cash payments to hire professional soldiers over relying on feudal levies. This change weakened the traditional feudal bonds and signaled a move toward a more centralized and financially based military system.

It is important to note that feudal obligations were not uniform; they varied based on local customs, the terms specified in charters, and negotiations between lords and vassals. For example, some knights held their land 'by serjeanty,' performing specific services rather than general military duty. Others might owe castle-guard service, requiring them to garrison a lord's castle for a set period.

Regional Variations and Adaptations

The experiences and roles of knights varied significantly across England. Regional differences in economy, culture, and local politics influenced how knighthood manifested in different areas.

In regions like the Welsh Marches and the Scottish borders, knights were frequently engaged in military activities due to ongoing conflicts and raids. These border knights developed reputations for toughness and adaptability, often operating semi-independently due to the distance from centralized royal authority.

In more peaceful and prosperous regions like East Anglia or the Southeast, knights might focus more on estate management, local administration, and participation in courtly life. In the Fenlands of East Anglia, for example, knights managed extensive agricultural estates and waterways. In the mountainous regions of the North, they dealt with challenges such as border defense and controlling rugged terrain.

These variations highlight the adaptability of the knightly class to local conditions, ensuring their relevance throughout changing times and contributing to the complex arrangement of medieval English society.

Impact

The origins of knighthood in England are rooted in a confluence of military innovation, social restructuring, and cultural integration. The Norman Conquest served as the catalyst for these changes, introducing cavalry warfare, feudal landholding, and continental chivalric ideals to England.

Over time, the knight evolved from a mounted warrior serving a military function to a multifaceted figure embodying martial skill, noble status, and moral virtue. By the late medieval period, advancements in military technology, such as the longbow and gunpowder, began to diminish the battlefield dominance of the knight. The rise of professional armies and changes in warfare tactics transformed the role of knights. Nevertheless, the ideals and social structures established during the origins of knighthood continued to influence English society well into the Renaissance.

Understanding the origins and development of knighthood provides valuable insights into the broader dynamics of medieval England—a society where land was power, loyalty was paramount, and the knight stood as a symbol of both feudal authority and chivalric ideals.